Perth is consistently ranked as one of the world’s most liveable cities, but what will happen as the population approaches 3.5 million?

Perth is consistently ranked as one of the world’s most liveable cities, but what will happen as the population approaches 3.5 million?

Committee for Perth chief executive Marion Fulker recalls the strong response she got from her fellow masters students at the London School of Economics last year.

Presenting on Perth’s longterm growth, she spoke about the city’s enviable lifestyle, before explaining the metropolitan area now sprawled 150 kilometres from north to south.

“They were really puzzled as to why Perth was setting itself up for what they see as failure,” Ms Fulker said.

“Why are you sprawling like that and killing off your beautiful natural environment and locking people into commuting long distances?”

Perth’s development as a sprawling, car-dependent city has been shaped by a series of planning schemes going back to the Stephenson-Hepburn Plan, which was drawn up in 1955 and designed to accommodate 1.4 million people by 2005.

The Corridor Plan followed in 1970, with the aim of channelling urban growth along self-sufficient corridors.

Metroplan, released in 1990, marked a shift in thinking. It recognised the need to create wider corridors of urban development, to try and consolidate the city.

That was followed by the Network City plan in 2004, which mapped out a connected city with higher densities around transport nodes.

It also flagged a target for urban infill, suggesting 60 per cent of new residential housing should be in established urban areas. That would have doubled the traditional level of about 30 per cent.

Setting targets

Directions 2031, released in 2010, set some hard targets to achieve a more compact and accessible city.

Key among these was the goal of 47 per cent urban infill.

Infill rates in the metro area have been trending higher over the past decade but have never come close to reaching that level.

The net infill rate (which accounts for demolition activity) has ranged from 28 per cent in 2012 to a high of 42 per cent in 2017 before falling back to 38 per cent in 2018, the most recent data.

Directions 2031 also set a goal to increase average residential density in greenfield development areas by 50 per cent, to 15 dwellings per gross hectare of urban-zoned land. This equates to 26 dwellings per net site hectare.

In 2018, the average density in greenfield growth areas was 22.2 dwellings per net site hectare – a significant increase over the decade but well below the long-term target.

It was against that backdrop that the current state government launched ‘Perth and Peel@3.5 million’ two years ago.

It mapped out a plan for accommodating 3.5 million people by 2050 – another target Perth is unlikely to reach, given the fall in population growth since the end of the resources construction boom and the halting of migration since the onset of COVID-19.

While the timing might change, Perth will eventually reach a population of 3.5 million people.

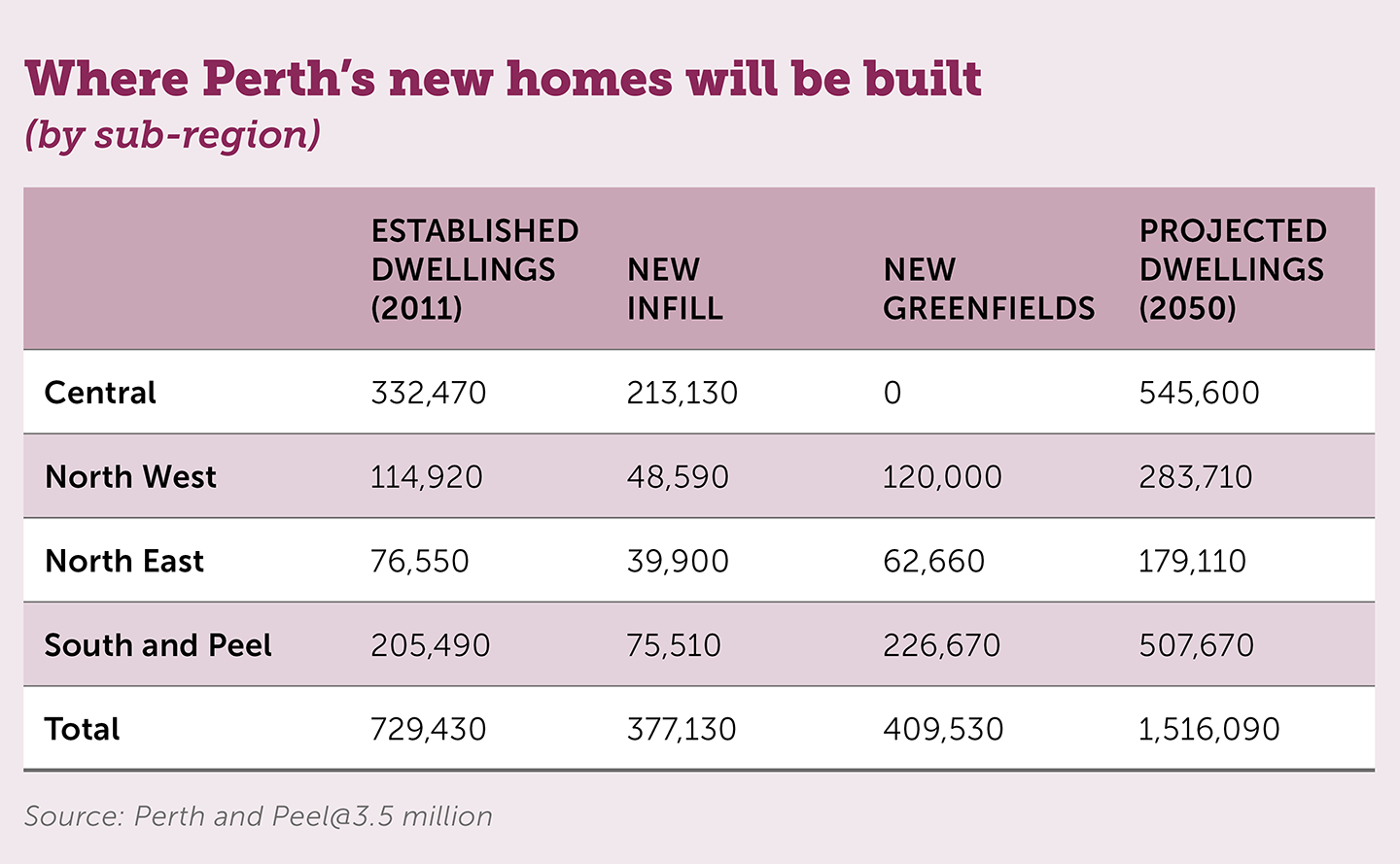

To accommodate that growth, Perth will need nearly 800,000 new homes.

If the government meets its 47 per cent infill target, nearly 380,000 dwellings will be built in existing urban areas. Most of these will be in the Central sub-region.

Most of Perth’s new dwellings (about 409,000) will continue to be greenfield developments on the urban fringe.

If infill stays around current levels (40 per cent), the number of houses built on the urban fringe will be even higher, around 470,000.

That highlights another challenge facing Perth, namely the mismatch between where people live and where they work.

The central metro area, which extends from Bayswater to North Beach, and from South Fremantle to Cannington, has more jobs than people, with a ratio of 139 per cent.

In contrast, the north-west sub-region, which encompasses Wanneroo and Joondalup, has a ratio of 49 per cent, meaning the number of jobs is only half the number of working-age people.

This is particularly important in Perth, which has one of the highest car use rates in the world, with more than three quarters of people travelling to work by car.

Policy response

Planning Minister Rita Saffioti acknowledges there is a way to go to meet the infill and density targets she inherited from Directions 2031.

“It’s definitely a work in progress,” Ms Saffioti told Business News.

The minister’s signature policies include Metronet, which features an expansion of Perth’s heavy rail network to places such as Byford, Yanchep and Ellenbrook.

“They are an acknowledgement that growth is occurring now,” Ms Saffioti said.

“People who want to live in those areas should have access to good public transport, so they are connected to jobs and opportunities.”

The state government is also overseeing a major expansion of the city’s road network.

Critics believe this will lock in Perth’s car dependency, but the minister is unapologetic.

“You need to invest in both; we are a spread-out city,” Ms Saffioti said.

She cites the Mandurah rail line as an example of public transport working in tandem with roads.

“If you don’t invest in public transport, your roads become unworkable,” Ms Saffioti said.

The state government has also been pushing to get more infill, in the process getting into a fight with municipalities including Subiaco and Nedlands.

“Most councils are on board,” Ms Saffioti said.

“No doubt the inner-city councils have a real challenge.

“Some have been proactive, others have been a bit resistant.”

To support more infill, the government is pursuing multiple reforms to a planning system that experienced planners such as Ross Povey says needs a big overhaul.

Tanya Steinbeck says the industry supports a balance of infill and greenfield development

Integrated planning

“The planning system in WA is set up for greenfield development, and that’s what we’ve seen a lot of in the last 40 years,” Mr Povey said.

“Infill is much more complicated; the system is not well set up for that.”

Mr Povey understands the frustrations felt by local councils, having previously worked at that level of government.

“I think the area where local governments get a bit frustrated is where the density argument is not backed up with infrastructure investment,” he said.

“Certainly in the central sub-region, where the largest amount of infill housing is occurring, that is an issue.

“There is no agreed plan for future transport investment in this region, there hasn’t been for a decade.

“The really good cities in the world have worked out that planning schemes need to better integrate transport and land use.”

Ms Fulker shares this concern, citing the example of Vancouver, in Canada.

“Density plus amenity plus mobility is what they get,” she said.

“They don’t get density with a promise of some things to come.

“It’s a more sophisticated conversation.”

Urban Development Institute of Australia state director Tanya Steinbeck also believes there is a need for better coordination.

“We have a planning framework that has been put together in isolation from an infrastructure strategy and in isolation from a sustainability or environmental strategy,” Ms Steinbeck said.

She welcomed last year’s establishment of Infrastructure WA, which is preparing a 20-year strategy for WA.

Ms Steinbeck also commended the establishment last year of the federal government’s Centre for Population, which she said would be a central source of truth for population forecasts.

Ms Steinbeck said the land development industry accepted the need for greater density.

“There is a cohort that will always want large homes and lots of space, but how do we also accommodate affordable housing, singles, couples, people downsizing?” she asked.

“We don’t have anywhere near enough one- and two-bedroom houses in Perth.

“To accommodate a population of 3.5 million by 2050, we need to deliver a lot more density.”

Ms Steinbeck also noted the high cost of delivering infrastructure on the urban fringe.

“We’ve gone as far as Mandurah and Yanchep with a rail line, how much further can we go?” While there are some opportunities in Perth for high-rise, she saw more potential in medium- density infill.

“That medium density space is the real opportunity, which we have done well in some areas, East Perth, the Midland redevelopment near the hospital, Subiaco near Centro.

“That’s the kind of density that I think is more acceptable to the community but there is still a place for high rise in the right location.”

Ms Steinbeck said her members were keen to see details of the government’s precinct planning policy, designed to support more density in defined areas such as around Metronet stations.

Ms Saffioti said infill had to change so there was a greater focus on busy precincts that could deliver high amenity rather than a blanket approach across entire suburbs (see page 10).

She also wants to see larger, better quality infill developments.

“We should encourage amalgamation of blocks for new developments, because big blocks give you an ability to deliver much better outcomes,” Ms Saffioti said.

The minister said the impact of density and well-planned precincts on business was often overlooked.

“High streets need people to survive and thrive; it means density so you have people who can walk to the strip to get their coffee and have their meal,” Ms Saffioti said.

A key element in the government’s agenda is the so-called planning reform action plan, with legislation being drafted.

“There is a lot of debate about particular buildings and their height, but that is usually a result of the local planning scheme and strategy,” Ms Saffioti told Business News.

“We want to make sure our schemes and plans are robust and reflect a good plan for each suburb.

“We need to engage people earlier when the schemes are developed, to avoid the arguments later about particular buildings “We don’t want frustration and surprises at the end.”

She said a key element in planning schemes was the transition from density to single residences.

Rita Saffioti is pursuing multiple reforms to get better outcomes

Land supply

The slowdown in Perth’s population growth has taken pressure off the city’s land supply, which is overseen by WA Planning Commission chair David Caddy.

However, Ms Steinbeck said it remained a long-term concern for the industry.

“David Caddy will tell you we have enough urban-zoned land to facilitate land supply until 2050; we’re not so sure,” she said.

The UDIA has reviewed one area of Perth and found that up to 25 per cent of land zoned ‘urban’ could not be developed because of issues such as land fragmentation or environmental constraints.

Ms Steinbeck said the UDIA was working with the government to review the underlying assumptions.

The state’s land supply is updated each year in the Urban Growth Monitor.

The latest edition said it would take 33 years to fully consume the current stock of urban-zoned land in the Perth and Peel regions, based on the historical development pattern of 30 per cent infill.

If the 47 per cent infill target were to be achieved, the existing urban-zoned land would last for 62 years.

Mr Caddy is confident the current land supply is adequate.

“When we talk about Perth and Peel developing to 3.5 million people, which it will eventually, we are making sure we have enough land that is zoned for urban development to accommodate that target, and a big part of that is the 47 per cent infill,” he said.

“We need to make sure the land is available and the infrastructure is in place to support that population.”

Ms Steinbeck said she did not expect the government to rezone any further land outside the existing planning boundaries.

“From what I see of this government, ‘Perth to Peel’ is effectively an urban growth boundary,” she said.

“They are not going to rezone any further sprawl.

“There is already a commitment, I think, to an urban growth boundary.”

However, Ms Saffioti said she was wary about the idea of imposing a hard boundary, noting research that suggested it may push up land prices.

“There is a lot of developable land available, plus Metronet creates new opportunities alongside rail infrastructure,” she said.

“That is my priority.”

Reflection

Ms Fulker said research commissioned by the Committee for Perth showed that Perth residents liked the city in its current form.

“We know from our work that people like Perth pretty much the way it is,” she said.

“The current policy reflects where the community is at.”

She added that the appreciation of Perth’s liveable environment had been heightened during the COVID-19 restrictions.

“We have really appreciated Perth as a place with lots of public open space, access to the river and lots of natural bush,” Ms Fulker said.

Ms Steinbeck has seen a similar community response.

“COVID has highlighted the importance of a really well planned and designed urban environment and the walkability and liveability of that environment,” she said, “We’ve started to use our local neighbourhoods, our cycle paths, our walking trails, our public open spaces, our local shops.”

Ms Fulker said the challenge for Perth was how to combine its current attributes with a much larger population.

“When Perth has another 1.5 million people, it still needs to feel like Perth,” she said.

“In most other cities, communities are really pushing back against trees being knocked down and habitat being eroded for more housing.”

She noted there had been considerable change, with more high-rise and more density in places such as Subi Centro and East Perth.

“We just don’t have enough of that,” Ms Fulker said.

“We are still building an excessive number of family-style dwellings when our demographics over 20 years have changed a lot.”

She said Perth needed more housing choices to ensure there were products that were affordable and suited different ages and stages of life.

Ms Fulker said there were a lot of positives in the state government’s approach.

“I think they’ve done well; the minister has a reform agenda and there has been widespread consultation.

“The minister has also been incredibly brave using her callin powers to get the outcomes she has wanted and been brave about making unpopular decisions.”

Ms Fulker’s concern is that the current policy settings, based on having a balance between infill and greenfield development, will not be adequate for Perth’s long-term future.

”They are certainly moving in the right direction if the goal is balance, but is that the goal?” she asked.

“Our target is only 47 per cent.

It’s not particularly ambitious.

“At the very least it should be 50 per cent and policies should be working across government to get there.”

She paints a worrying picture of what may happen without a major shift.

“Perth will grow out, not up, and the region will suffer from the ill effects of land obesity with limited options for intervention,” Ms Fulker said.

“Greater Perth will be fixed in a cycle of urban sprawl and car dependence.

“This approach will come at a cost to the environment, the community, taxpayers and to Perth’s prized quality of life.”