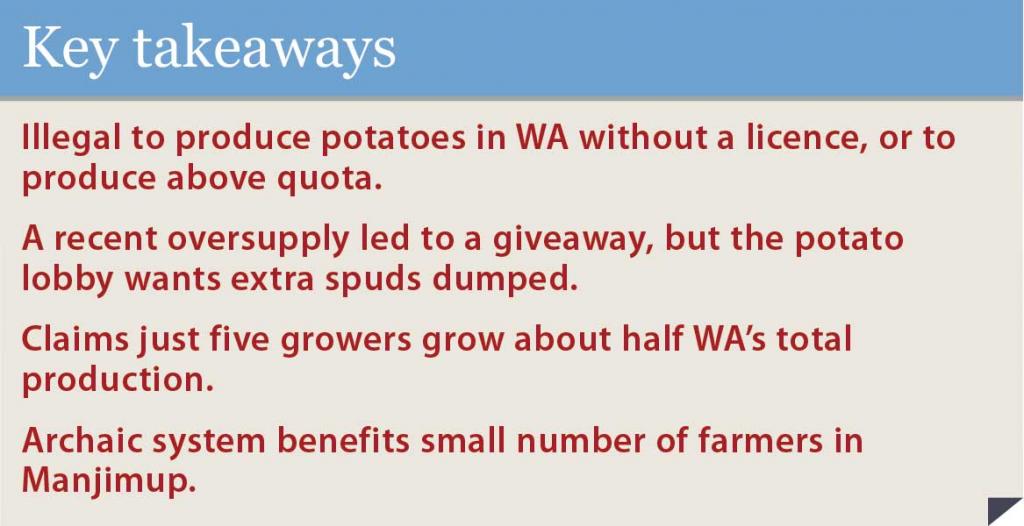

The regulation of potato production in WA has the business community bemused at how such an anachronism can survive.

The regulation of potato production in WA has the business community bemused at how such an anachronism can survive.

Galati Group managing director and farmer Tony Galati won’t back down in his latest fight with potato bureaucracy, the Potato Marketing Corporation, preferring to go to jail than pay a fine for doing what he loves.

Nor will he let the battle stop him from growing his business, with plans for a new store in metropolitan Perth, another in Bunbury, and a growth opportunity in banana plantations.

The latest dispute comes after Mr Galati gave away hundreds of tonnes of potatoes through his Spudshed outlets in January, running afoul of legislation created in 1946 because of a post-WWII potato shortage.

Mr Galati is critical of the potato corporation’s inability to effectively deal with a bigger than expected surplus.

“If there’s a glut of potatoes, what do you do with them?” he asked.

“You sell them cheaper and move them on.

“And the reason they’ve got a glut of potatoes … those guys should’ve realised three months ago there was an oversupply because we all had good weather and our yields were all good yields.”

It seems some growers may have overplanted in the expectation that the corporation would be deregulated, following adverse findings last July by the Economic Regulation Authority.

Mr Galati said the corporation should have dropped the price in October to clear the market and get rid of the oversupply.

However others in the industry take the view excess potatoes should not go to consumers, including Potato Growers Association executive officer Jim Turley.

“Excess potatoes should be dumped,” Mr Turley said.

“We don’t want to lower the price … we’re already the cheapest price in Australia so why penalise everybody else?

“It’s bad news to oversupply – it’s bad for the environment, it’s bad for everyone. Absolutely (growers should be prosecuted) if they overplant.”

Mr Galati said he expected the potato corporation would try to claim damages.

“We’ll fight them all the way,” he said.

“And if I get prosecuted and there was a fine, I’d take a stance, I wouldn’t pay it and they’d have to put me in jail.

“I’d probably be the only potato grower in the world to be jailed for growing potatoes … for trying to produce a competitive product to put in our market.”

Mr Galati said his stance was driven by the impact of the bureaucracy on consumers and other growers, most especially in terms of the cost impost.

Mr Galati said his stance was driven by the impact of the bureaucracy on consumers and other growers, most especially in terms of the cost impost.

“There’s a 20 per cent levy the board charges ... you drop the price 20 per cent on potatoes, that’s a big saving for the consumers,” Mr Galati told Business News.

Dropping the price would also make potatoes more competitive with other carbohydrate sources, such as pasta and rice, he said.

The Potato Marketing Corporation has a suite of strategies it uses to maintain a high price for its growers, including the imposition of barriers to entry for potential competitors.

For example it is illegal to possess more than 50 kilograms of potatoes in Western Australia without a licence.

Securing a licence would involve a one-off cost of up to $500,000, while annual supply is regulated by a system of domestic market entitlements.

An entitlement would generally sell for anywhere between $100 and $500 a tonne.

Mr Galati said the benefits of the potato corporation were concentrated among growers in an area with poor soil, while farmers who grew in better conditions, such as in sand, produced a better quality spud but received the same price.

“Consumers aren’t getting a benefit out of this (the PMC), only a handful of growers down in Manjimup,” he said.

“That’s why they keep it.

“The guys that grow in the sand are subsidising those guys down there.

“There are so many growers in WA that want the opportunity to grow spuds but they’re not allowed to grow them.”

Mr Turley said about 60 per cent of licences were held in the area around Manjimup, but disagreed that there was a system of cross-subsidies in place.

He said machinery, water and chemical costs would more likely be prohibitive to new entrants than restrictions on production levels.

Mr Turley said the state’s growers would soon introduce a new variety, which he expected to be popular with consumers.

The corporation used surveys to determine what consumers wanted, he said, rather than relying on price signals.

Mr Galati told Business News it was difficult to grow boutique varieties because farmers could not earn a sufficient return.

Chamber of Commerce and Industry chief executive Deidre Willmott agreed the corporation was unnecessary.

“It is ridiculous that the Government regulates potato sales in Western Australia,” Ms Willmott said.

“These restrictions have limited growth, innovation and competition in the WA potato farming industry.

“The Economic Regulation Authority’s report estimated that the net cost of the regulated potato market to the State economy will be $33 million over the next 15 years – that is simply unsustainable.”

The corporation did not respond to requests for comment.

A diverse business

Grocery retailer Spudshed, which forms part of the Galati Group, expanded its footprint in Perth recently with a new store in Innaloo, the sixth outlet of its type.

There are plans to open a further store in the metro area, and one in Bunbury, Mr Galati told Business News, and they could open as early as this year, depending on approvals.

He said Spudshed stores catered to more than 90,000 customers a week, and supplied cheaper food by embracing products that might be slightly out of specification for major retailers.

The group is also expanding banana production in Kununurra.

Mr Galati said WA imported nearly 50,000 cartons of bananas every week, mostly from Queensland, with local production around 3,000 cartons per week.

After planting around 40 hectares this year, the group has forecast production of 50,000 cartons of bananas, with that number expected to increase significantly in the next few years as more land is planted.

That’s in addition to the thousands of hectares of vegetables, mangoes and table grapes grown by the Galati Group.

Mr Galati said building his business to its current size had been challenging, and time consuming.

“A lot of people ask us how we created such a successful business … and it seems like we’ve done it in the past 25 years,” he said.

“But a normal person would work 40 hours a week.

“We do an average of 120, 130 hours a week, so if you multiply that it’s like 90 years of work.

"We’ve got a passion; we enjoy what we do, my brother (Vince) and I.”