After decades of planning, several marina projects proposing more than 900 boat pens are starting to take shape, but challenges remain.

After decades of planning, several marina projects proposing more than 900 boat pens are starting to take shape, but challenges remain.

Few developers would stick with a project if it took more than 40 years to work through from inception to construction.

Thankfully for backers of the Ocean Reef Marina, the state government has proved more determined than most, since the idea was first proposed in the 1970s.

The start of site works in August was a significant milestone for the marina, which received the environmental green light in August 2019 and construction approval from the City of Joondalup last February.

This is despite recent community opposition to the project from groups such as Save Ocean Reef.

It’s not the first time a marina project in Western Australia has faced pushback from the broader public, with widespread support historically required before such sensitive developments proceed.

“Projects of Ocean Reef Marina’s nature are complex,” Joondalup Mayor Albert Jacob told Business News.

“History has shown that projects of this nature have an average gestation period of 30 years from when the idea would have been raised until firm initiation of the project materialising.

“They are very dependent on the will for it to proceed, not only from the wider community but also from all levels of government.”

Concept plans for the marina have undergone several iterations during the past four decades, following a number of community forums, surveys, workshops, reference groups and open days, with the state government committing $126.5 million in funding for the life of the project in 2017.

That funding was the nudge the project needed to get off the ground, with finalised plans proposing approximately 12,000 square metres of retail and commercial space, a dedicated marine enterprise precinct, new community club facilities and a coastal pool.

The marina will have capacity for 550 boat pens, 200 boat stackers, and large moorings suitable for super yachts.

The project is expected to generate more than $900 million in private and public sector investment, with significant residential development earmarked for the site.

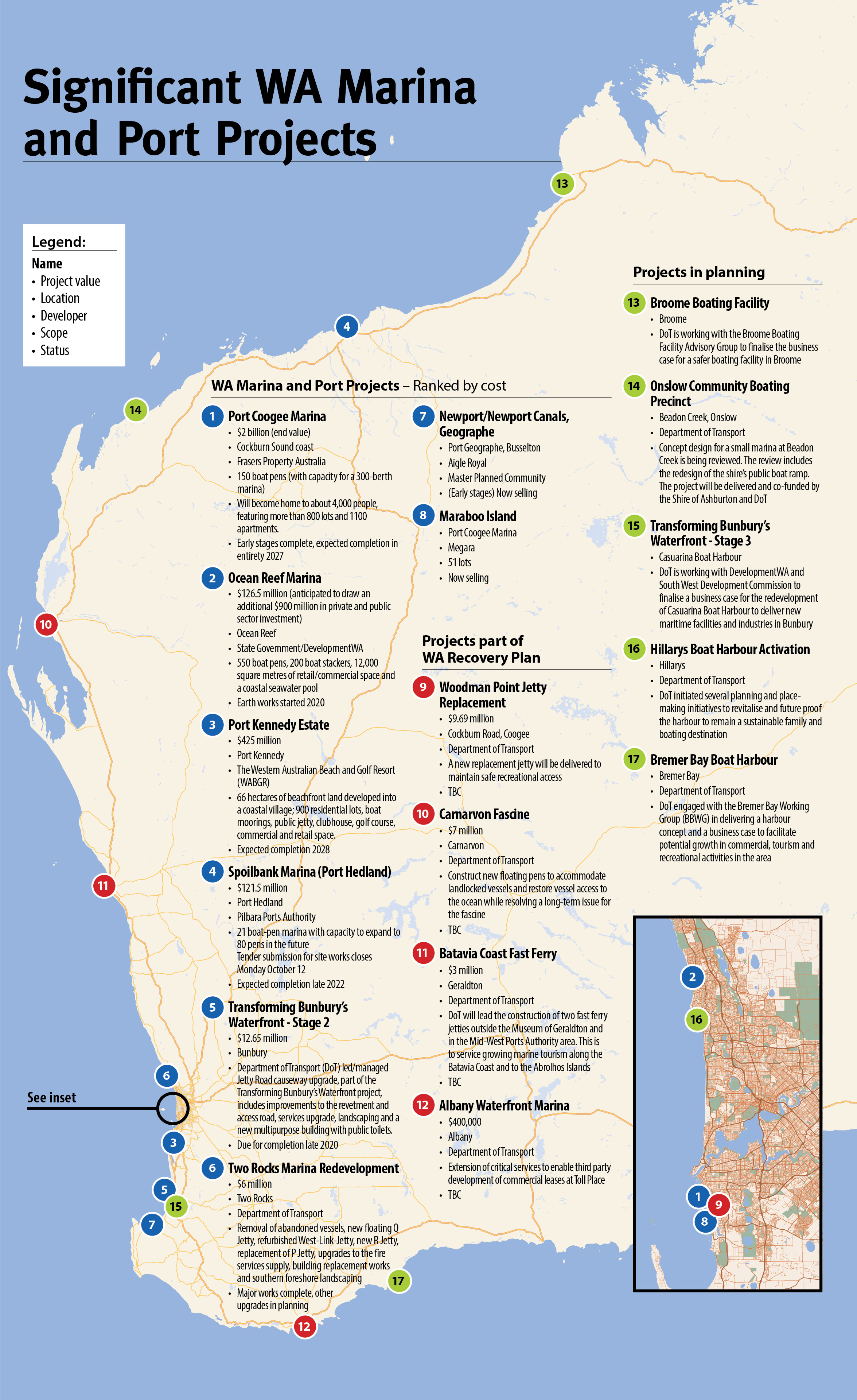

The project is part of a more than $2 billion pipeline of marina and port projects along WA’s coast, which will collectively create more than 900 boat pens over the next few years (see map).

The Ocean Reef Marina is not an outlier in terms of long lead times between initial planning and the turning of the first sod.

The Spoilbank Marina in Port Hedland, which was given development approval last month, has been under discussion since the mid-2000s; and the $425 million Port Kennedy project broke ground earlier this year, following nearly three decades of negotiations between the state government and a Singaporean developer over the transfer of 66 hectares of beachfront land.

While there were myriad reasons for project delays, Department of Transport director maritime planning Corey Verwey said cost was a common roadblock for most marina developments.

The DoT manages 34 maritime facilities along the WA coast, including Hillarys Boat Harbour and Fremantle Fishing Boat Harbour, and is also leading a number of coastal infrastructure projects, including the $12.65 million (stage two) transformation of Bunbury Waterfront and the $6 million Two Rocks Marina redevelopment.

“There are high capital costs associated with delivering this infrastructure and equally high maintenance costs, and this is a significant consideration,” Mr Verwey told Business News.

“[Additionally] site selection, planning and design and modelling are important in reducing the impact of facilities on the environment, and critical to achieving environmental approvals.”

Despite these lengthy processes, the economic and tourism benefits appear to be worth the effort.

Lands Minister Ben Wyatt said the latest modelling showed the Ocean Reef Marina would result in an estimated $3 billion boost to the broader economy, creating 8,600 construction jobs and 900 ongoing jobs after the build.

“This is exactly the sort of project we need to help keep our state moving forward during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Mr Wyatt said.

“The development will also bring more housing options to the local area, providing more choice for residents.”

A construction working group, which includes local organisations and residents, was recently established to provide direct community input during early works, however, time will tell if Save Ocean Reef’s protestations will have any further impact.

But as history has shown, completing a marina project in WA has been anything but smooth sailing.

Historical echo

In the 1980s, protestors lay down in front of bulldozers in an attempt to halt early site works for what would become Hillarys Boat Harbour.

A newspaper article from June 1985 titled ‘Beach group to fight on’ provides a glimpse into the opposition the project faced, which involved asking for donations to fund potential legal

intervention.

A case study undertaken by Committee for Perth in 2011 sought to offer a non-partisan overview via historical documentation and an assessment of concerns expressed by local activists at the time.

The committee found that, when the Shire of Wanneroo held a public meeting on the proposal, 200 of the 250 attendees voted in favour.

However, within two months of council granting development approval, local residents formed powerful lobby groups, with key objections including: inadequacy of environmental assessments; concerns the new harbour would deprive Perth of a natural and safe swimming beach; and, ironically considering events of 2020, that it was in the wrong location and should be developed at Ocean Reef.

In January 1985, the Environmental Protection Authority released the Hillarys Boat Harbour Environmental Review and Management program. It received 4,211 public submissions, seven times higher than the average response.

Although opposition was fierce, Hillarys Boat Harbour was completed in October 1986 at a cost of $13 million (more than double the originally estimated $4 million to $5 million). It now attracts up to 5 million visitors annually and employs about 1,200 people.

While some concerns have proved prescient (marine habitat loss as a result of breakwaters and dredging), others were more subjective.

For example, the natural beach was replaced by a sheltered man-made alternative, with the number of people actually using the beach reportedly up substantially.

Most importantly, the case study highlights a perennial dichotomy in WA.

“Western Australians love to have access to waterfronts with amenity such as commercial, tourism and leisure activities, yet we fear any change to our treasured coastline,” the case study said.

Community objections were not enough to stop Hillarys Boat Harbour, but they have been successful in halting coastal developments elsewhere.

In 2018, the 75-hectare mixed-use Mangles Bay Marina, a joint venture by Cedar Woods Properties and LandCorp (now DevelopmentWA), planned for Point Peron, was blocked.

The project had already been granted environmental approvals at both state and federal levels, however, 403 public submissions (out of a total 496) against the project, coupled with statements issued by the Conservation Council of Western Australia expressing concerns for the colony of penguins nearby, was enough to stop the project.

Despite the knock-back, Cedar Woods state manager WA Ben Rosser said it had not deterred the company from marina-style developments, which, while posing environmental and planning challenges, were backed by strong demand.

“Where pristine coastline or waterways are involved there will always be heightened concern about the interruption of these environments,” Mr Rosser told Business News.

“Unfortunately there have been past examples whereby approvers and developers had got it wrong and detrimental impacts remain to this day.

“In the management of community opposition, we have found the best approach to be one of transparency and honesty in the provision of information and open consultation.

“While there will always be vocal minority opposition to development, we never lose sight of the existence of the non-vocal silent majority who will adopt an objective view to the information provided through this approach.”

Cedar Woods has undertaken several other waterfront developments, including the transformation of a degraded swamp into Mariners Cove in Mandurah: a canal residential development of 987 blocks across 198ha, with 50 per cent of the area reserved for conservation and open space.

Within Mariners Cove, Cedar Woods’ Hamptons Edge community features 25 homes, each with private boat moorings.

Urban Development Institute of Australia WA chief executive Tanya Steinbeck said Western Australians valued their pristine coast and it was understandable locals were cautious about coastal development.

However, there was untapped potential, she said, with infill activation remaining limited, pointing to Scarborough as one of the only near-city suburbs creating new residential, commercial, and recreational opportunities.

“While we need to protect vulnerable areas, providing access and recreational opportunities in appropriate nodes along the coast is critical to meeting demand for lifestyle, boating and other marine activities,” she said.

“There are opportunities in existing areas such as Cottesloe where local politics has hampered redevelopment opportunities and left an iconic location lagging behind other areas.

“Port Coogee in Cockburn and Rockingham are also examples of where foreshore redevelopment has vastly improved the surrounding area and provided much-needed amenity for residents and visitors.”

Click on map to enlarge.

Demand for coastal living

The Port Coogee Marina currently under development at Cockburn Sound, led by Frasers Property Australia, is one of the state’s largest marina developments. It’s expected to deliver more than 800 lots and 1,100 apartments, with capacity for a 300-berth marina.

WA-based developer Megara has bought in to the project and is now selling lots for its man-made island estate.

Maraboo Island comprises 51 lots in total and the initial release of 10 northern canal lots and 12 beachside homes in late 2019 sold within three months, which led to the early release of 10 Maraboo Cove lots, 70 per cent of which sold within the first month, Megara said.

Director Jamie Clarke said it was the group’s most successful project in recent years.

“In this environment, it’s certainly sold easier than some of the other projects we’ve had,” Mr Clarke told Business News.

“I absolutely think that certain areas should be left untouched, but there are other areas that definitely warrant thoughtful, environmentally sensitive and sustainable development options.”

Port Coogee Marina has obtained clean marina accreditation from the Marina Industries Association (an international, voluntary program), with an active marina management team maintaining the waterways, which are home to more than 80 fish species and a selection of hard corals.

“We’ve got a vast coastline and there are opportunities to develop in the right way,” Mr Clarke said.

“One of our upcoming projects will have significant engagement with the ocean as well, so we are certainly very positive about oceanfront properties.

“It’s certainly not getting any easier (for marina-style development) and I don’t expect it will.

“But you could do a little project in the middle of the suburbs, which has just as many challenges.”

Development challenges have been compounding for the Port Geographe Marina, just north of Busselton, which started development in the 1990s.

The marina has fronted a range of issues, including the accumulation of seaweed on beaches, which led to the state government committing $30 million to reconfigure entrance groynes.

Aigle Royal Group purchased an already heavily excavated land parcel adjoining the marina in 2015, after the previous site owner went into liquidation when the liability for coastal management exceeded the value of its security bonds.

Aigle general manager Brad Brashaw said responsibility for coastal management had since been transferred to the state and local government, which had made it a more attractive development opportunity.

A predominance of internal canal lots were initially proposed in the original development plan, however, Mr Brashaw said Aigle identified a more feasible opportunity. That involved avoiding potential water quality and water flushing issues by instead filling in the majority of the existing hole that had been created for more waterways with sand, to create a more traditional dry residential product, that would interface with a reduced number of canal legs and a new waterfront centre.

Since acquiring the balance of the previously stalled project, Aigle has completed rejuvenation earthworks (importing substantial volumes of sand) and built the first stage, comprising approximately 70 lots, which it said was close to sold out, with less than 10 lots remaining.

Aigle has also been progressing approvals for the amended development masterplan on the remaining portions, but now fronts another challenge; State Planning Policy 2.6, which governs coastal planning based off modelling of anticipated erosion and future sea level rise.

Part of that policy involves prescribed floor levels of 3.8 metres above sea level for the area - more than 1.3 metres above previous conditions and existing surrounding lot and infrastructure levels.

Mr Brashaw said that not only posed problems for Aigle, which had paused development based on feasibility and practicality, but also all future projects for the area, which, on average stood at 2.5 metres above sea level or below.

“We have never said we don’t agree with the science or the issue, itself; we’re saying that in the long term, it’s a much broader issue that cannot be addressed by just us - or other individual private developers,” Mr Brashaw told Business News.

Mr Brashaw said authorities acknowledged those implications, and Aigle was working with the City of Busselton and other key agencies, which were undertaking a Coastal Hazard Risk Management and Adaptation Planning (CHRMAP) process to investigate strategies, such as sea walls, to address the issue over the next 100 years.

“Developers should be part of the solution, but it’s a much broader issue and requires a more strategic, viable and practical approach than simply requiring individual developers to fill their new develoment proposals (with sand) to solve the long-term problem,” he said.

“This needs much broader support from state and federal government; it’s an issue for Australia’s entire coastline.”