There are many moving parts that need tweaking to make the NDIS function at its best.

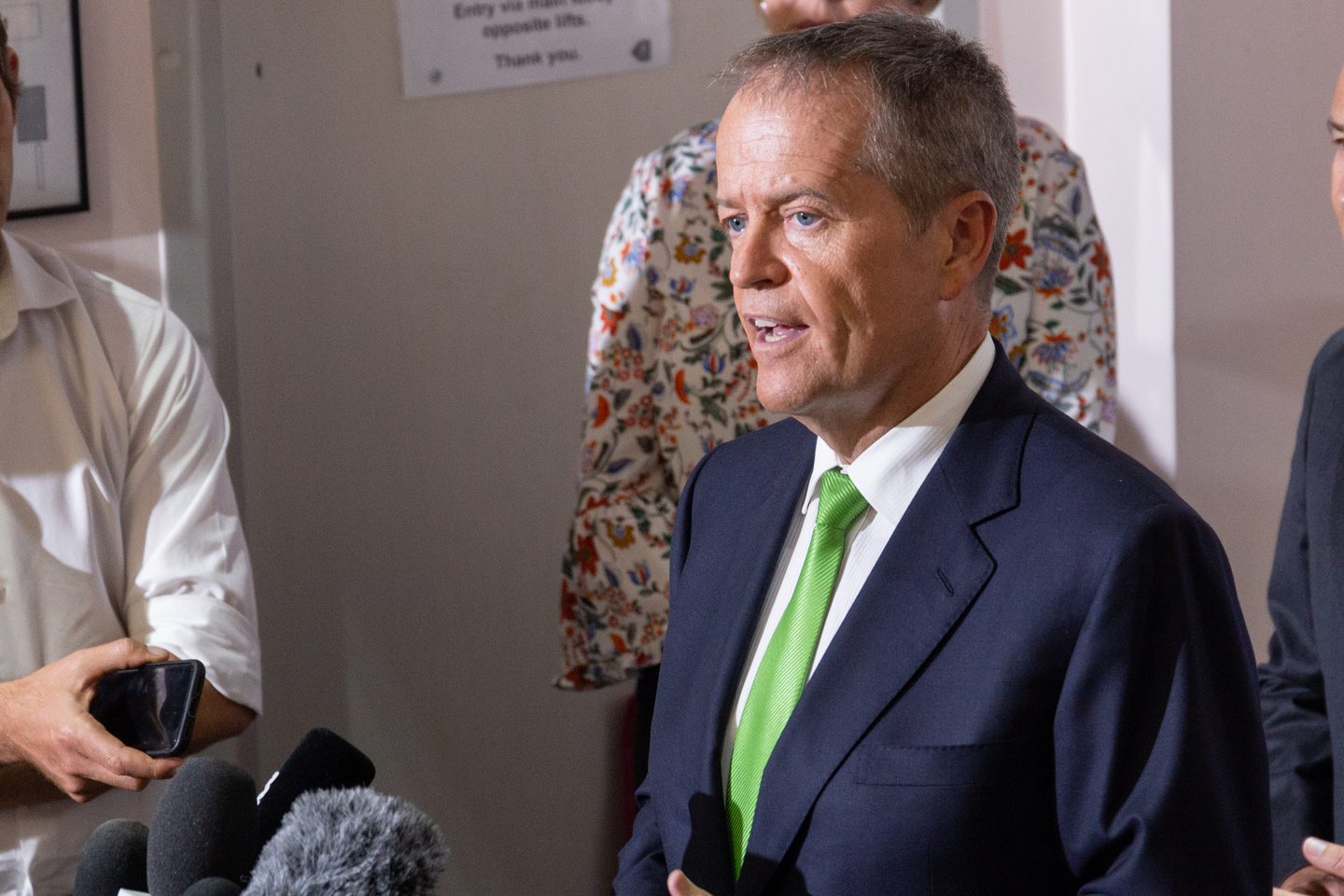

T HE minister responsible for the National Disability Insurance Scheme, Bill Shorten, sounds like he wants to make some changes.

“There’s a massive traffic jam of profoundly disabled people occupying hospital beds, which is costing the taxpayer a fortune and it’s diabolical for people with disability,”

Mr Shorten said recently.

“We’re going to take the power out of the hands of faceless bureaucrats; let’s sort it out.”

While many would have found those words refreshing, it would be an oversimplification to think that beating up the NDIA is going to fix things.

The issue of hospital discharge delays involving people with disability is not an NDIA problem and neither is it a state government problem.

It is a national problem and there is no silver bullet. Even the most efficient NDIA decision making and the best hospital discharge processes in the world won’t make any difference if the patient does not have suitable accommodation to go to.

This is the key barrier to reducing discharge delays and getting otherwise medically fit people out of hospital and mental health units and back ‘home’.

The housing system in Western Australia is almost designed to make it impossible for a person with disability to source accommodation that meets their needs in a short period of time.

There are few truly accessible houses on the market (sale or rental) and, even where they do exist, there is no way to definitively identify them.

Sadly, there is also evidence to suggest we still live in a world where landlords would rather rent to a tenant with average needs than a person with disability.

It is challenging for anyone needing government support (let alone a person in crisis and stuck in hospital) to navigate the system and ascertain what state or federal programs they are eligible for and whether they have any accommodation available.

For those seeking to access social housing in WA, there is also limited accessible social housing stock, and in any event, my understanding is that people with disability are not generally given priority on the Department of Communities waitlist.

The NDIA does fund specialist disability accommodation (SDA), which is an excellent use of the private sector to create a supply of accessible disability housing.

However, WA is still behind the rest of the country in terms of supply due to its late entry into the NDIS.

There are also challenges created by a still-maturing market and WA legislation that never considered SDA.

The SDA program is also small, funding only 6 per cent of participants in the NDIS, with the other 94 per cent being required to seek mainstream housing options.

Finally, for many people with disability a house is no good if the person is unable to access the support required to live in it.

The NDIS has routinely been cutting funding across the board for the past 12 months, often to the point where participants cannot afford to fund the level of support required to bring them home from hospital.

There is no doubt that the NDIA decision-making processes around plan funding are too slow, and this is a critical reason many people with disability end up languishing in hospital, at the cost of thousands of dollars a day to taxpayers (not to mention their mental health), while they wait for funding.

There are green shoots, however.

Several state government initiatives are in play that recognise the systemic lens required, and the recent establishment of The Disability Reform Ministers’ Meetings as a forum for the Commonwealth and state and territory ministers to drive national reform is a real positive.

This challenge is not a dissimilar to that experienced in the aged care sector almost 15 years ago and the solutions required are probably not too different.

The cost of long delays in discharges for otherwise entirely medically fit people is disproportionate for everyone involved: the person with disability, their family, taxpayers and the hospital system.

Rather than a blame game, we need genuine engagement on a collaborative cross- government, cross-sector approach that uses a systems lens to identify barriers and solutions.

• Amber Crosthwaite is a commercial lawyer specialising in seniors living, aged care and disability.