The history of value adding in the iron ore sector is a litany of missed opportunities.

The history of value adding in the iron ore sector is a litany of missed opportunities.

Australia’s largest mining sector is arguably the biggest failure when it comes to value adding.

However, that’s not to say the big iron ore miners have ignored downstream processing altogether.

The sector has invested billions of dollars in a succession of iron and steel projects, none of which have stood the test of time.

These projects were designed to meet commitments to downstream processing made under state agreements.

(click here to view a PDF version of the 12-page liftout)

One of the earliest state agreements was signed in 1952 by BHP, which subsequently built a steel-rolling mill in Kwinana, followed by a blast furnace and pig iron mill in the late 1960s.

These plants processed iron ore mined at Cockatoo Island and Koolyanobbing, in the days when the Pilbara was just emerging as an iron ore province.

The iron and steel plants lasted until the 1980s, when they were shut down as part of a major restructuring of the sector nationally.

BHP’s rivals focused on the Pilbara for their early investments in downstream processing.

Hamersley Iron (now Rio Tinto) built a 2 million tonnes per annum pellet plant at Dampier in the late 1960s.

Cliffs Robe River Iron Associates (also now part of Rio Tinto) followed with construction of a similar plant at Cape Lambert.

Both pellet plants were shut down in the late 1970s when high oil prices pushed up their costs.

BHP tried something similar at Port Hedland in the 1990s, when it invested $2.5 billion in its ill-fated Boodarie Iron project.

Boodarie was designed to convert iron ore ‘fines’ (with about 62 per cent iron content) into ‘clinkers’ (90 per cent content), an ideal feedstock for steel mills.

Built between 1996 and 1999, the project never ran smoothly – it faced cost over-runs, commissioning difficulties, and operational issues.

Designed to produce 2.3mtpa, its peak output was 1.7mtpa in 2004.

By that stage, BHP had completely written-off the value of the project.

The last straw was an explosion in 2004 that killed a worker and led to the plant’s immediate shutdown, with 490 employees and about 500 contractors losing their jobs as a result.

Boodarie was on its last legs when Rio proceeded with its next attempt at downstream processing: its ambitious HIsmelt pig iron project.

Rio and three joint venture partners invested about $1 billion in HIsmelt over 25 years.

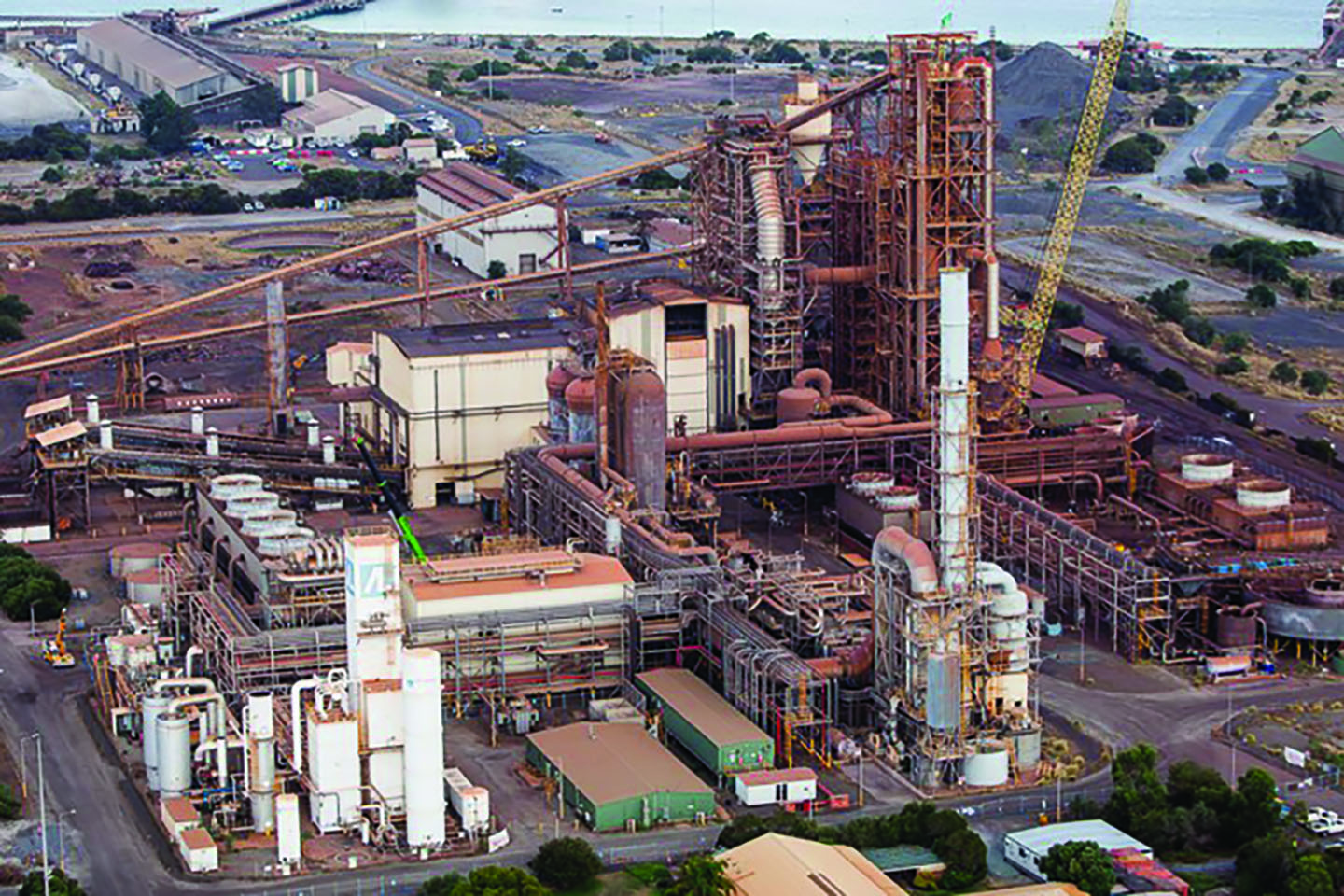

Most of that time was spent on research and development and running a test plant, before they committed in 2002 to build a full-scale commercial plant – on the same plot of land as BHP’s old steel mill.

Officially opened in 2005, HIsmelt was designed to produce around 800,000tpa of high quality pig iron (96 per cent iron content). Its actual production was about half that.

HIsmelt never stacked up commercially and Rio pulled the pin in 2008, at the height of the GFC.

While the Kwinana plant is history, the HIsmelt technology is not.

China’s Shandong Steel Group has recently reported technical success with its Molong HIsmelt plant, though its commercial performance is not clear.

Looking ahead, an opportunity for the sector lies in the processing of low-grade magnetite ore to produce a high-quality feedstock for steel mills.

Chinese companies CITIC Pacific and Karara Mining pioneered magnetite production in Australia. It has not been a happy story, however, with massive cost blowouts during construction and big losses during production.

Despite that history, Fortescue Metals Group will begin construction of its $US2.6 billion Iron Bridge magnetite project later this year.

Iron Bridge is designed to produce 22mtpa of product with a high (67 per cent) iron content, which will be blended with the lower grade ore from the company’s existing hematite mines.

That combination would deliver a substantial pricing premium.

If FMG succeeds where others have failed, it will put pressure on Rio and BHP to consider similar moves.