We will need to look decades ahead to choose between bigger regional cities or a much denser Perth when WA has more than 5 million residents.

Would a million people living in the Pilbara be a sustainable economic option for Western Australia?

What about in a chain of regional cities through the South West?

Or should they be packed into high-rise buildings in Perth?

Western Australia, and the nation as a whole, should be looking decades ahead to consider the right path, according to Australian Urban Design Research Centre co-director Julian Bolleter.

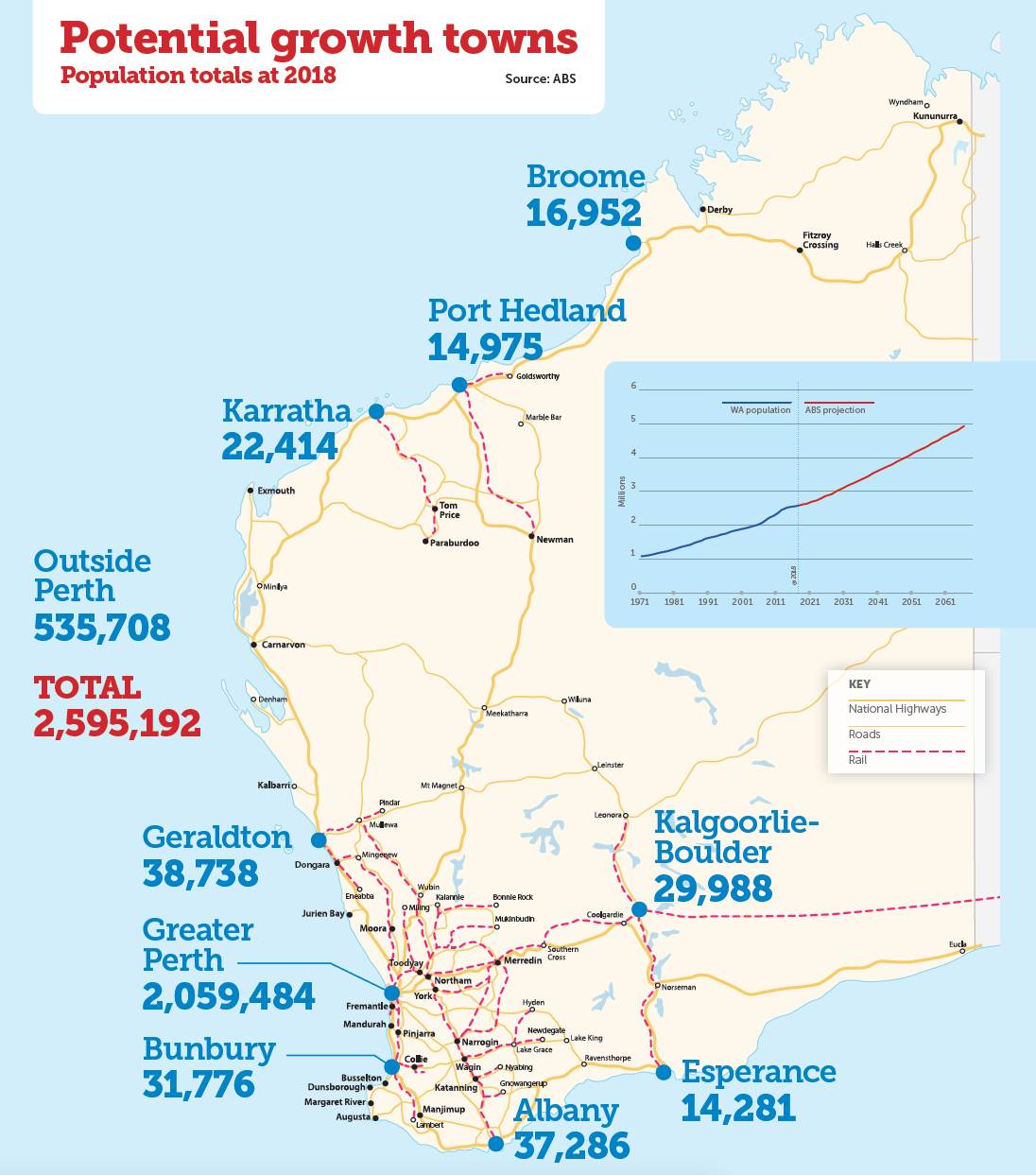

Projections from the Australian Bureau of Statistics show WA’s population should hit about 5 million in the late 2060s, in a base case.

The national population is expected to double in the next 80 years to about 50 million.

AUDRC’s recent research focus has included identifying a range of population distributions for analysis by experts.

Dr Bolleter said they were now running a survey to seek responses from the general public.

The hope is this will inform a national strategy for the decades ahead.

Dr Bolleter said Perth with 5 million, or possibly 6 million, people might not be ideal.

“It’ll be a pretty big city, bigger than Sydney is now,” he told Business News.

That brings challenges in terms of changes to living arrangements and congestion.

Infrastructure Australia predicted in 2018 that congestion costs in Perth could rise from less than $2 billion annually in 2016 to be around $5 billion in 2031.

Density could bring benefits in terms of agglomeration economics, where idea ecosystems can grow naturally, Dr Bolleter said, which was particularly beneficial in a service-focused economy.

But density would not be enough to house all the expected population growth.

“It’s unlikely to be solved by infill development alone,” Dr Bolleter said.

“There’s a public sullenness about development.

“Our love affair with the Australian dream (of home ownership) continues.

“(And) the pandemic has brought home to people … how much benefit suburban living can bring.

“I think the mood is shifting and I don’t think it is shifting towards density.”

Similarly, dropping most of the 25 million additional Australians expected by the end of the century into Sydney or Melbourne will bring major challenges.

There’s a variety of alternatives, with regional WA front and centre in many of them.

The most popular option with planners, who were consulted for the research, was devolving population into satellite cities, Dr Bolleter said.

That would include Mandurah, Bunbury, Northam, Toodyay and towns on the north coast.

Similar examples can be found in Newcastle or Wollongong in New South Wales, or the commuter towns around London.

Another option would be a chain of smaller cities through the South West, linking Albany, Bunbury, Margaret River and other smaller towns into a mega region through a major rail connection.

“It sounds a bit ridiculous now but you have to imagine by mid-century, Perth’s population could be 5 million,” Dr Bolleter said.

Planning ahead would include securing easements for rail connections early, to be prepared for when the demand arises.

“It’s not necessary yet, (Bunbury) is certainly not crying out for a high speed rail link,” he said.

“But things will turn and we need to be ready.”

One option that has been less popular with planners is big population growth in the Pilbara municipalities of Port Hedland and Karratha, and in the Kimberley’s Broome township.

This proposal would be threatened by climate change, Dr Bolleter said.

“Not just (the north’s) liveability will be compromised, its viability,” he said.

This issue required sustained analysis, and it was important not to be motivated by politics or intuition, as governments had often been, Dr Bolleter said.

By contrast, professional company director Ken Perry, who formerly led contracting company Brandrill, strongly believes in the need to develop the north of WA.

“We need to occupy our north and develop our north,” Mr Perry said.

“We don’t need another one million (or more) people in Perth.

“I’m looking north but Albany is a cracker of a place.

“The benefit (of population growth) is they become isolated no longer.”

Mr Perry said fly-in, fly-out workers were not necessarily the most likely to move, and governments would need to show leadership to encourage other Western Australians into the regions.

He rejected the hot climate as an issue.

“It’s very hot in Bali, in Singapore ... people get used to it,” Mr Perry said.

“Look at North Queensland.”

The area around Cairns had about 250,000 people, he said.

There was also a security imperative to develop the north, too, because it was resource rich and very open.

Emerging and declining

One topic of considerable debate is allocating public spending between communities which are growing, against managing decline in those where populations are either ageing or shrinking.

The median age in the Wheatbelt is 44, compared to 32 in the Pilbara, according to the most recent census data.

ACIL Allen director of WA and NT John Nicolaou said sustainability of the population was essential to supporting a community.

“(Regional development) is a long-standing issue for all states in the federation ... there’s a global trend towards urbanisation,” Mr Nicolaou said.

“Sustainable population can only come through opportunity and economic benefit.

“Without jobs in the regions, you’ll struggle to build communities.

“It’s a challenge ... and will remain that way in the future.

“But it’s not insurmountable.”

Creation of economic opportunities should be prioritised over social investment, he said.

“Social investment will always come if economic opportunities are there,” Mr Nicolaou said.

In areas supported by broadacre farming, improvements in technology were reducing the need for labour, while remote operations in resources could have a similar impact.

“The first principle we have to go back to, unfortunately, is: are there economic opportunities to support a regional centre long term?” he said.

Work to diversify the state’s economy potentially provided an antidote to this challenge, with tourism one opportunity.

Mr Nicolaou said tourism, as a service industry, was more labour intensive than many other sectors.

Technological change to support remote work would also support population decentralising, AUDRC’s Dr Bolleter said.

Future infrastructure

While Dr Bolleter has highlighted the potential need for better rail links between Perth and nearby regional centres in the longer term, changes in the way people drive will need consideration.

There are revolutions expected in the decade ahead in road transport, including the rise of autonomous vehicles and replacement of the combustion engine.

“The electrification of our transport network will be central to a looming shift in how we move around our cities and regions, and how we manage the health of our communities,” RAC general manager public policy and mobility Anne Still said.

“When the topic of electrified transport is raised there is often ferocious debate, and a lack of consensus and direction is slowing progress.

“Australia’s economic, social and environmental outlook will become increasingly hinged to how we respond to the electrification of our transport network.

“Without action, we risk being unprepared to manage the impacts and opportunities of an electric future.”

Ms Still said ensuring there was sufficient charging infrastructure in regional areas, and their integration with the energy network, would need consideration.

She said work had been undertaken to map out the optimal infrastructure approach for electric vehicles across regional WA.

One further issue would be ensuring infrastructure for autonomous vehicles, which may require access to 5G mobile networks, depending on the exact technology solution which gains widespread adoption.

On the autonomous vehicle front, testing has been done on sites in the Wheatbelt and Pilbara to trial technology that can detect departure of these vehicles from their lanes.