It was the week before Christmas 2021 when melanoma researcher Professor Jonas Nilsson from the Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research urgently contacted Genomics WA.

He wanted a cancer patient’s tissue sample’s DNA analysed for mutations as quickly as possible.

The patient had an aggressive cancer that had spread to her lymph nodes, but the skin cancer surgeons did not know where it came from, where the primary cancer was located.

After a multidisciplinary tumour board meeting it was decided that a patient tissue sample be sent to the internationally renowned melanoma researcher.

They wanted to know if the DNA mutations could provide any clues as to where the cancer originated.

Without knowing the primary cancer, they couldn’t confirm the treatment that would best target it.

The hunt was on.

Western Australia has only had a dedicated genomics facility since 2020.

Before Genomics WA was established, researchers sent tissue samples interstate or overseas, a process that prevented some samples being tested.

But a joint partnership between The University of Western Australia, the Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research and Telethon Kids Institute with critical Federal and State government funding had enabled the set-up of a genomics laboratory with next-generation sequencing technology in Perth.

The facility is accessible to all WA research institutions and is accessed, not only to analyse human tissue but also plant, animal, soil and even marine samples.

Anything that has DNA can be analysed. The technology is very costly to use but the information it produces is priceless.

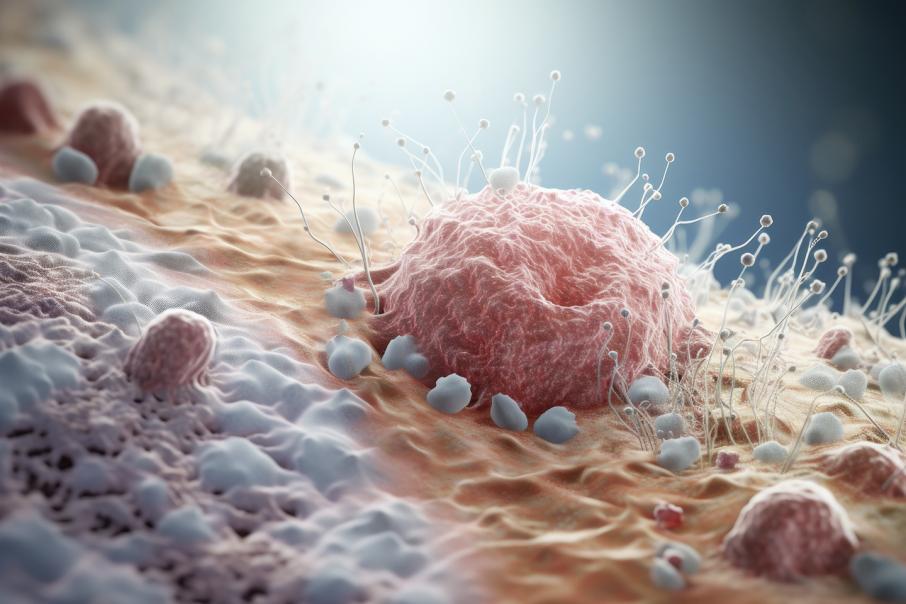

In relation to cancer samples the technology can analyse thousands of cells from tumours using single cell sequencing and also examine billions of genetic sequences using gene sequencing to determine the genetic make-up of each tumour to provide new insights into how cancer cells evolve and interact with normal cells.

As every tumour is unique, this level of detail is transformative. Through genomic analysis researchers may be able to predict a tumour’s response to drugs, to identify new drugs to combat cancer and develop innovative ways to kill cancer cells.

In the past two years, Genomics WA’s multidisciplinary team of biologists and computational scientists has been examining different samples, including cancers which have poor outcomes, and cells from a variety of disorders.

Already 28 different organisations, including a number from interstate and overseas, have sent samples for sequencing that have resulted in more than 2.6 million cells being processed.

This includes samples sent from non-biomedical researchers from disciplines including environment, plant and agriculture, fisheries and synthetic biology.

For example, the technology has enabled new ways to analyse the DNA of field coral.

The Australian Institute of Marine Sciences studying the health of corals, and whale sharks, are accessing the next generation sequencing technology because the Genomics WA laboratory is one of few facilities in the world that can generate high quality data from field coral samples.

It is giving previously unknown insights about the health of coral at Rowley shoals.

Coral is a good indicator of change in the environment due to human activities or global warming, but coral collected from the field is difficult to process for sequencing.

However, Genomics WA modified an existing process commonly used for human samples, to create a customised way for processing DNA from field coral samples.

Ultimately this work will enable marine scientists to understand the health and resilience of marine and coastal ecosystems across northern Australia.

This was the type of work in the queue in the run-up to the Christmas break when Professor Nilsson presented the patient tissue sample for analysis.

The patient had been operated on but for the continued management by oncologists it was critical to know the origin of the tumour.

Genomics WA was already working with Prof Nilsson to identify mutations in the DNA of WA skin cancer patients that give a cancer cell a fundamental growth advantage.

The new sample could be sent in with other samples that were going to be analysed; the timing was perfect.

However, it was touch and go that the samples could be processed before the Christmas break.

But within a week, they had data delivered to Prof Nilsson’s team.

The cancer in the lymph node was not a skin cancer.

The DNA analysis showed the primary cancer was in the patient’s reproductive system.

In addition, clues on how the cancer had developed were unravelled, demonstrating impact of a tumour virus.

Clinical lab examinations independently confirmed that the patient had the virus. A pathologist confirmed the diagnosis.

The discovery led to a drastic change being made in the clinical management of the patient.

In Professor Nilsson’s laboratory at the Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research a quiet cheer went up. In record time he had been able to provide critical information that would potentially change a patient’s cancer journey.

The collaboration of doctor, researcher and genomics experts produced an outcome for a patient through a seamless process unavailable in WA only two years ago.