ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL: Foreign investment, free trade and a skilled workforce have helped WA tap its enormous oil and gas reserves, to the benefit of the entire country. This article is part of a special series to mark Business News' 25-year anniversary.

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL: Foreign investment, free trade and a skilled workforce have helped WA tap its enormous oil and gas reserves, to the benefit of the entire country. This article is part of a special series to mark Business News' 25-year anniversary.

When Woodside Petroleum let contracts for the Goodwyn A gas platform in 1990 the project cost was reported to be about $US1.6 billion.

That outlay on the expansion of the North West Shelf Venture included a third gas liquefaction train at the venture’s Karratha gas plant, and construction of the platform itself.

The scale of offshore oil and gas developments has increased by an order of magnitude since Goodwyn opened in 1995, with new projects in the ten of billions of dollars, while Western Australia’s energy exports have surged dramatically.

From two operating LNG trains in the early 1990s, WA now has 11 trains in operation, with one other close to production and another in planning.

The massive increase in production capacity has meant annual LNG exports for the state rose from about $1 billion in calendar year 1993 to be $19 billion in the 12 months to June 2018, according to the state government’s Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety.

In addition, crude oil and condensate exports increased from $1.1 billion in 1993 to $5.6 billion in the past year.

Much of the money invested in new capacity has come from foreign sources.

US-based Chevron, for example, led two projects worth a total of $US88 billion, almost all of which came from international businesses.

Dutch company Shell, Japan’s Inpex, and US-based ExxonMobil are among the other companies that backed new LNG capacity in WA.

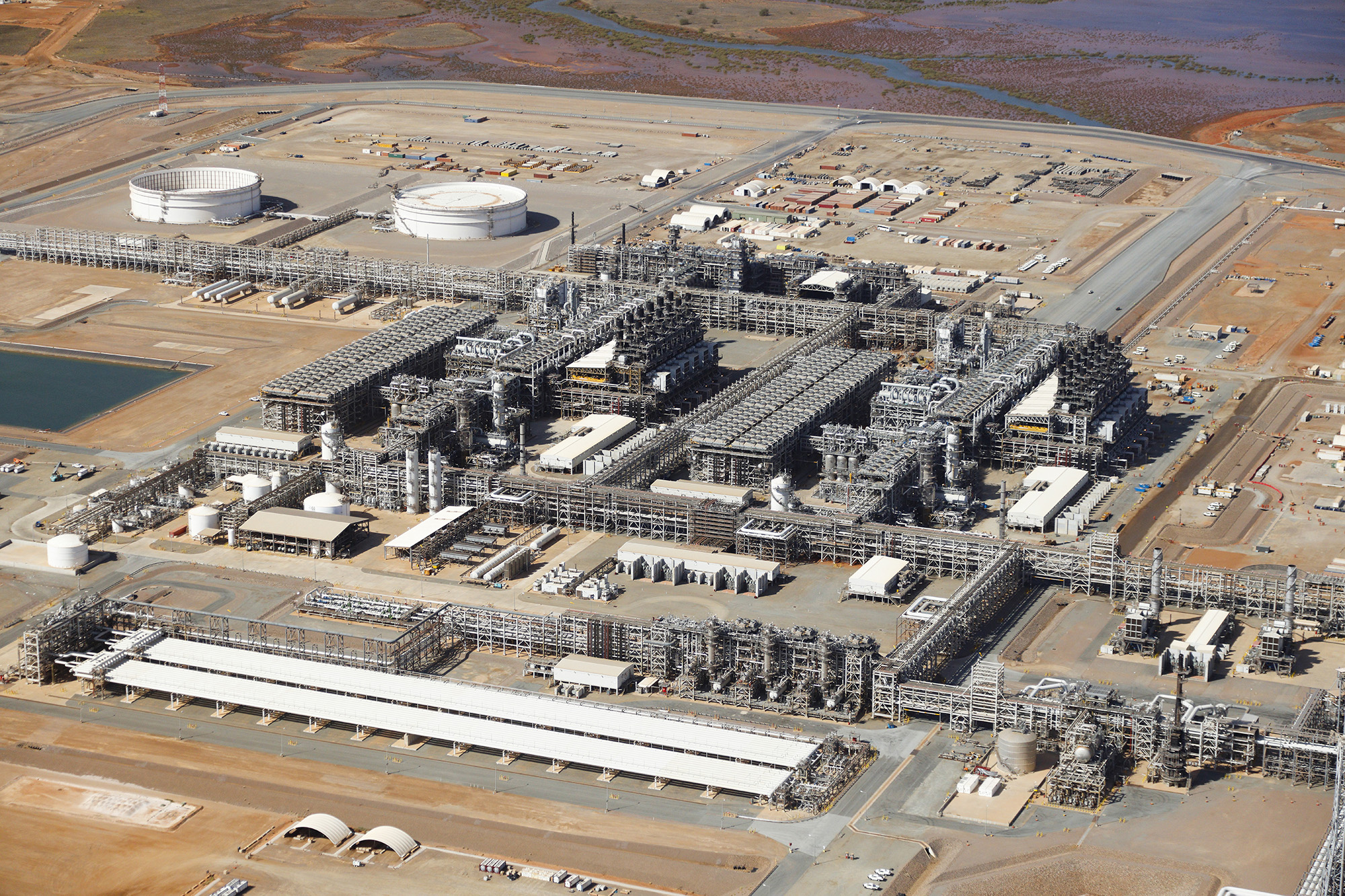

The big projects comprised Inpex’s Ichthys (although processing takes place in Darwin), Woodside Petroleum’s Pluto, Chevron’s Gorgon and Wheatstone, Shell’s floating plant Prelude and new trains at North West Shelf Venture’s Karratha.

All opened in the past decade.

Production started at Wheatstone train two earlier this year.

Although a portion of the new gas produced is reserved for domestic use, the bulk of it is exported.

With about 53.4 exajoules of gas in the Carnarvon Basin alone, enough to supply 150 years of domestic demand at the current level, the state has plenty available for sale overseas.

An additional consideration is that much of that gas would never be economic if produced for the local market because of the high level of capital investment required to extract it.

The economic impact of the export industry is considerable.

For example, the biggest LNG project was Gorgon, estimated to cost about $US54 billion.

It will add about $440 billion to Australian gross domestic product in the three decades to 2040, according to a 2015 report by consultancy ACIL Allen.

That creates local jobs and incomes during operation, generates tax for government, and ultimately improves living standards for all Australians because of the foreign currency generated.

The economic benefit is supplemented by spending on community infrastructure, with about $250 million allocated to the town of Onslow, while a further $1 billion was invested into research and development, according to the ACIL report.

In the longer term, ongoing maintenance spending and the need for new fields to sustain production will also create economic activity for the state.

A recent example was Chevron’s decision earlier this year to proceed with phase two of the Gorgon project, with about $US5 billion to be spent on new subsea infrastructure.

Demanding industry

Debate in recent times about changes to the federal government’s Petroleum Resource Rent Tax regime, around energy company profitability, and the social licence to operate perhaps reflects a lack of understanding of the significant effort required to get projects completed.

The challenges can be best illustrated by the level of cost blowouts in major builds and by the number of projects that were delayed or failed to proceed during the boom years.

Perhaps the most notable example is the Browse LNG project, led by Woodside Petroleum and located in the Browse Basin.

Plans to extract gas from the Brecknock, Calliance and Torosa fields, the first of which was discovered in 1971, have undergone numerous permutations.

In 2010, Woodside, Shell and other partners decided on an onshore development model, with the processing facilities to be based in an industrial zone at James Price Point, near Broome.

The selection of that location by the state government was controversial, with protests from environmental groups, with a potential splintering of native title representatives only narrowly avoided.

Plans for an onshore development were dropped in 2013 because of high costs.

A second iteration was to use a floating LNG plant, similar to that currently being developed at the nearby Shell Prelude field.

That was dropped in March 2016 amid low oil prices.

This year, Woodside has been moving towards a new proposal for Browse, which will tie-back the fields via a very long pipeline to the existing North West Shelf Venture facilities at Karratha, which will have spare capacity in the middle of next decade.

It won’t be the first development to use a huge pipeline, which in this particular case will measure about 900 kilometres.

Japanese company Inpex built a similar length pipeline for its Ichthys project, to take gas from Browse Basin to Darwin.

That was announced in September 2008, with Inpex saying the choice of Darwin for an onshore processing plant would bring certainty.

Inpex had been in an ongoing debate with the Carpenter state government and environmental groups about a previous plan to build the facility on the Maret Islands.

Projects that did not eventuate were Equus, which was then under the control of US-based Hess Corporation, and Bonaparte FLNG, which was then a partnership between GDF Suez and Santos.

There was also considerable ambition in terms of exploration during the late 2000s, with companies seeking to find gas to give projects greater scale.

Those projects that did go ahead generally suffered major cost blowouts, and delays, with the most prominent being Gorgon.

It cost 46 per cent more than planned, at $US54 billion.

Those complexities show that, despite the big headline revenue numbers, oil and gas may not be the licence to print money some may consider it to be.