Opinion: While politicians are showering favoured industries in cash this federal election, voters should remember the recent train wreck of Carnegie Clean Energy as a reminder that subsidies for businesses can flop badly.

Opinion: While politicians are showering favoured industries in cash this federal election, voters should remember the recent train wreck of Carnegie Clean Energy as a reminder that subsidies for businesses can flop badly.

There appears to be a historic regression towards economic interventionism ahead of the federal poll on Saturday.

From the Labor opposition, $4 billion for childcare, $1 billion for manufacturing, $1 billion for hydrogen, $200 million for batteries, and $10 billion more for the Clean Energy Finance Corporation.

The incumbent government hasn’t been pristine either, with a $1 billion small business equity fund, following a $2 billion small business loan securitisation scheme announced last year.

This weekend, there was a $500 million home buyer deposit guarantee, which earned criticism in some corners for its potential to encourage risky loans.

I’m reminded of a representative from one battery mineral miner who, during an interview with me some years ago, was adamant the state government should give support to the company’s plans to value add in WA.

When asked why the government should subsidise an uncompetitive industry, he responded that it could be competitive, although it would be cheaper to do it overseas.

After more prodding, he admitted that they just did not want to dilute shareholder capital.

Brilliant.

Now, we have at least six major value adding battery minerals projects in the pipeline in WA.

How expensive would industry support have been, and utterly pointless, given so many companies decided to invest here anyway?

When the subsidised business can be competitive without support, it just makes larger profits at society’s expense.

On the other hand, if a business needs a subsidy to survive, then by definition, the cost to society of its production exceeds the revenue.

That’s why economists will generally argue for subsidies only to balance externalities.

If the massive programs proposed are enacted post-election, successful businesses will effectively be paying tax (and consequently be made less competitive) to aid businesses that are otherwise already uncompetitive.

The outcome is fewer jobs and less income created overall.

Then there’s Carnegie.

Carnegie was given grants to work on a series of projects including a wave power farm in Albany.

There was $60 million from two federal agencies, including the Clean Energy Finance Corporation, and at least $2.6 million lost by the state government.

Those large wads of cash were basically dropped to the bottom of the Southern Ocean in March when the business called in administrators.

Carnegie paid $13 million in its 2016 acquisition of Energy Made Clean, which reportedly could have been sold for only $200,000 this year.

If a business had money to overpay on a takeover bid, did it need taxpayer support for research?

The CEFC also generously loaned Pilbara Minerals $20 million in June 2017 to build its Pilgangoora lithium mine.

That mine was a great success, and reducing carbon emissions a noble goal.

But I’m not sure how subsidising the supply chain for overseas battery manufacturers is going to help cut Australia’s carbon emissions.

Childcare

On to Labor’s policy.

Increasing support for childcare is intended to lift the pay of childcare workers and improve accessibility.

Childcare workers earn an average $865 a week in Australia, which is not a big salary.

It is, however, higher than the median personal income in Australia, which was $662 per week as of the 2016 census, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, so half of Australia’s population above 15 years of age earn less than the average childcare worker.

Government absolutely has a role to ensure opportunity for the most vulnerable in society.

Surely this measure is poorly targeted, however.

Families earning below $69,527 will be $1,400 a year better off, Labor argues.

Fair enough.

But families earning between $100,001 and $174,527 will be $1,200 better off on average.

That’s hardly a group that is desperately in need, which is why the opposition opposed tax cuts for families earning more than $120,000.

Effectively, they’re taxing those people more to pay a bit back via childcare spending.

Yes, high childcare costs are among the disincentives for parents to return to the workforce after having children.

High tapering rates of welfare payments and increasing marginal tax rates are problematic, too.

Labor will partially solve the cost issue while making the tax rate problem worse for a wider group of people.

Outcome

Higher subsidies will ultimately raise the cost of childcare provision without improving quality or availability.

They reduce incentives for businesses to keep costs under control or improve services, particularly when the company gets the cash directly.

Why keep prices down if the government will pay, in some circumstances, 100 per cent of the cost (up to a standardised price of $141 a day)?

Finland is a practical example.

Public spending on childcare is reportedly 0.6 per cent of GDP, yet more than 15 per cent of an average family's income still gets spent on childcare.

Labor promised to crack down on unscrupulous providers, except the problem isn’t about businesses being unscrupulous.

It’s simply that, as we saw in the case of Carnegie, there’s less incentive to operate efficiently when truckloads of extra cash is coming through your front door.

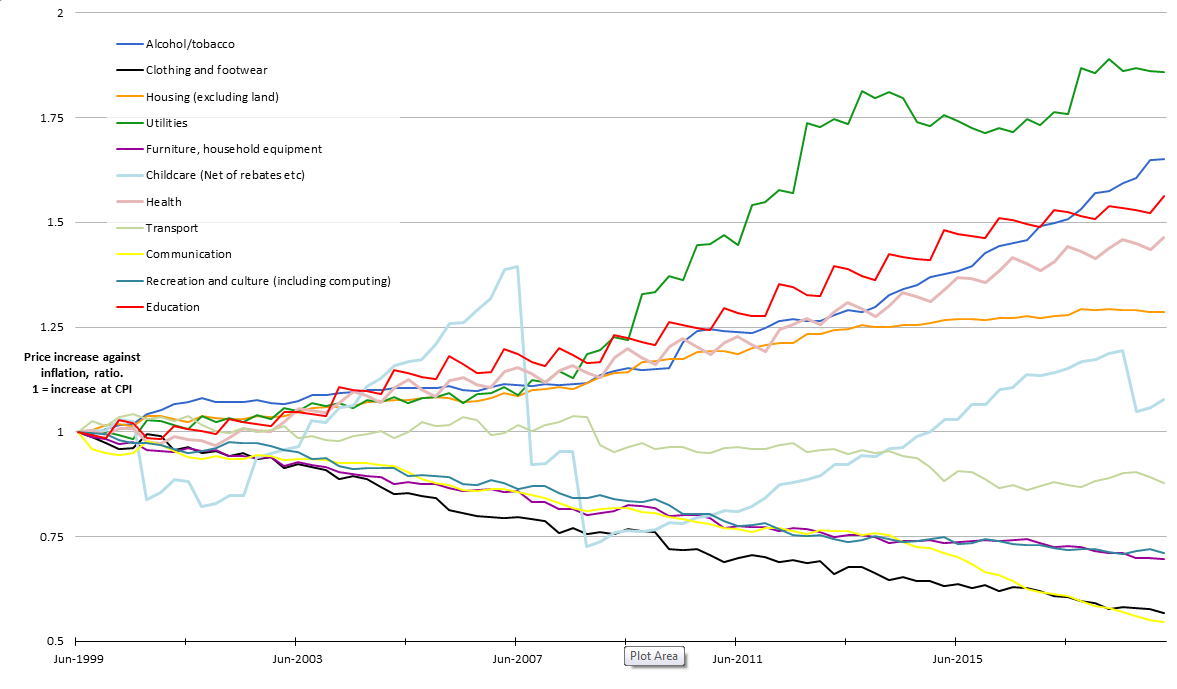

Consumer price data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics shows utilities (86 per cent), education (56 per cent) and health (46 per cent) are among the sectors with the highest price increases in the past 20 years (see graph).

There’s a consistent theme.

Sectors with high price rises are not trade exposed, are often more labour intensive and - most relevant - generally have higher government intervention.

Childcare looks good by comparison (7.8 per cent), except that is misleading.

The ABS price trend benefitted from a big fall in 2007 caused by a change in the way the childcare tax rebate was administered.

Action

To make childcare more accessible, we should focus on supply side reforms.

The Australian Childcare Alliance reportedly says the industry is squeezed by high regulated staffing ratios and National Quality Framework requirements- maybe that’s a good place to start.

The second option is to increase competition and give consumers more choice by broadening the scope of what parents can claim a rebate, subsidy or deduction for.

If a parent wants to have a university student from down the street mind the kids for a couple of days a week, because that’s all they can afford, why shouldn’t they have the same rebate as someone who uses childcare?

Governments should give the parents scope to choose the quality and cost that suits them, rather than choosing it for them.