With public consultation on the state government’s Westport project starting this month, we look back at more than 20 years of planning for an outer harbour at Kwinana.

With public consultation on the state government’s Westport project starting this month, we look back at more than 20 years of planning for an outer harbour at Kwinana.

In February 2004, the WA Planning Commission issued an information brochure on development of a new outer harbour at Kwinana.

Based on trade trends at the time, it said the inner harbour at Fremantle was expected to reach capacity by around the year 2017.

Fremantle Ports made the same prediction in June 2004, saying growth in container trade meant the inner harbour would reach capacity within 10-15 years, around 2017.

Alannah MacTiernan, who was planning and infrastructure minister at the time, made similar predictions.

In July 2006, Ms MacTiernan said Perth would need a second port within 10 years as the inner harbour reached its capacity.

The Carpenter government’s response to the looming capacity crunch at the existing harbour was to release a preferred option for development of a major new container port at Kwinana.

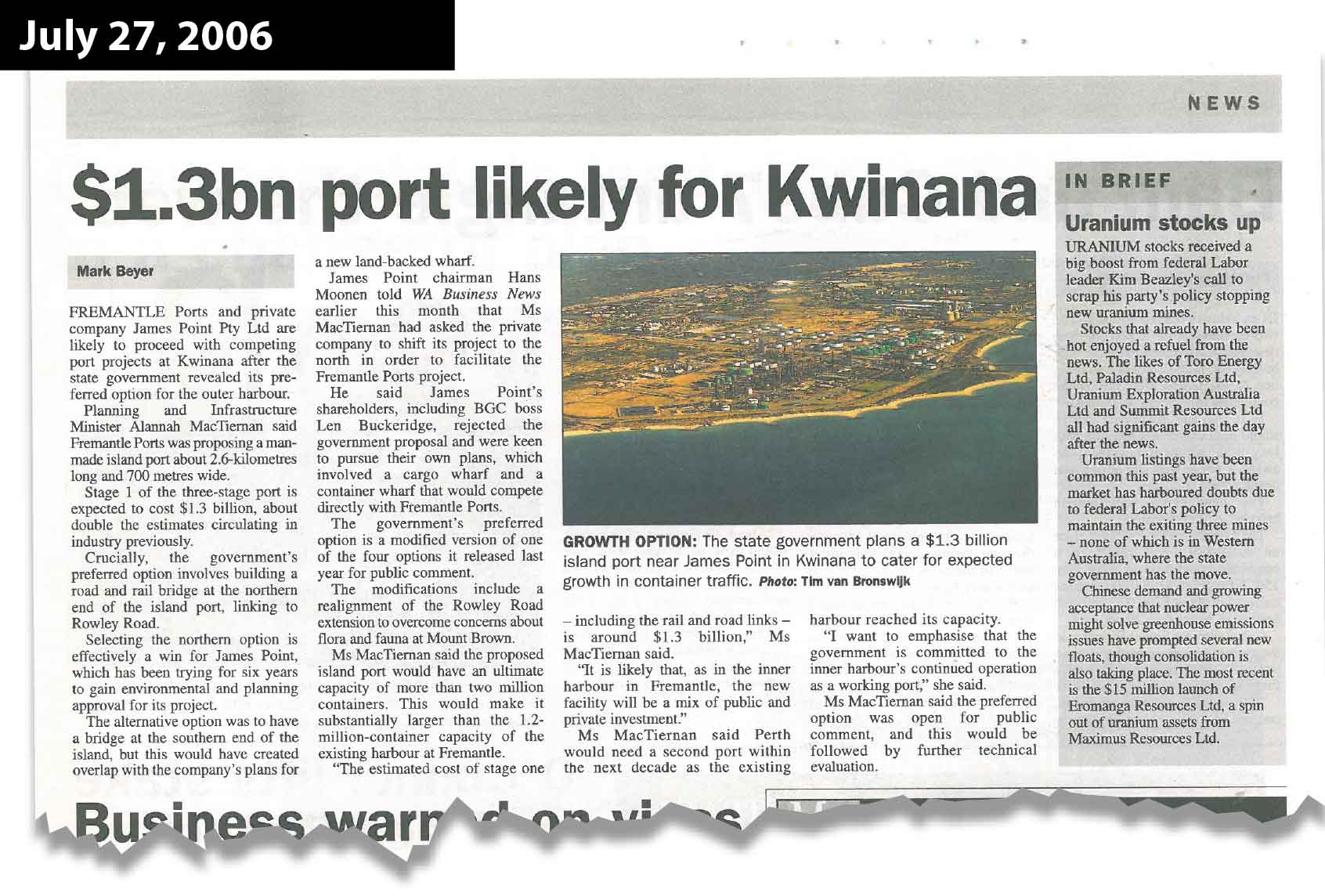

The proposed facility – depicted in the Business News articles reproduced above – was to be a man-made island in Cockburn Sound, about 2.6 kilometres long and 700 metres wide.

“It is envisaged the three-stage project would have an ultimate capacity of more than 2 million containers, compared with the 1.2 million capacity for the inner harbour,” Ms MacTiernan said at the time.

“The estimated cost of stage one – including the rail and road links – is about $1.3 billion.”

More than a decade later, the inner harbour at Fremantle is yet to reach capacity, and the state government is still planning for an outer harbour at Kwinana.

Private port

Before looking forward to the current planning challenges, it’s worth revisiting some of the complexities and intrigue that have characterised port planning during the past 20 years.

In 1997, the Court government advertised for the private sector to build, own, and operate new port facilities at Kwinana.

In 1999, the James Point consortium was named as the preferred tenderer, and in December 2000 it signed a formal operating agreement.

That timing proved critical, because Richard Court’s government lost power in February the next year, replaced by Labor’s Geoff Gallop.

Labor attacked the James Point project as a union-busting scheme, in part because its backers included the founder of construction company BGC Australia, the late Len Buckeridge, who was renowned for being tough on unions.

Despite having a frosty relationship with the Labor government, James Point pushed on with its plans, gaining environmental approval in 2004.

That complicated the planning task facing the state government, as James Point held development rights over the only stretch of coast suitable for a land-backed wharf.

The proposed island port avoided overlap with the James Point plan (see drawing above) and threw up the possibility of two ports being developed around the same time.

A combination of planning delays and shifting priorities – along with continued debate over the capacity of the existing harbour at Fremantle – meant neither project proceeded through the noughties.

The election of the Barnett government in 2008 meant all plans came under fresh scrutiny, but with the resources construction boom in full swing, the outer harbour was not a high priority.

In 2012, planning minister John Day said the WA Planning Commission was seeking a consultant to assess the various project proposals.

At the same time, the James Point consortium continued to plough ahead, with chairman Chris Whittaker telling Business News in April 2013 he hoped to start construction within months.

The death of Len Buckeridge in 2014, and the launch of the Perth Freight Link project a few months later, changed the complexion of the port debate.

Perth Freight Link, which amounted to an upgrade of the road freight network leading into Fremantle – was vigorously opposed by Labor.

It was concerned the project would cause major environmental damage to the Beeliar Wetlands and claimed the upgraded roads would not deliver a coherent long-term solution to Perth’s freight needs.

In the lead-up to the 2017 election, Labor ramped-up talk of an outer harbour, which would reduce freight volumes into central Fremantle.

Westport

Despite extensive planning over the past two decades, the McGowan government has established the Westport taskforce to develop a new plan.

Planning Minister Rita Saffioti formally launched the Westport taskforce in September last year, with Nicole Lockwood appointed as chair.

At the time, Ms Saffioti said the taskforce would complete the planning for the McGowan government’s long-term outer harbour freight vision.

“The multi-agency Westport taskforce will outline a long-range vision to guide the planning, development and growth of both the inner harbour at Fremantle and the future outer harbour at Kwinana,” she said.

“Together, they will develop answers to key policy questions surrounding the location, size, operating model and timing for a future port.”

The taskforce itself has been at pains to say it has an open mind.

“A common misconception is the Westport taskforce has already developed a preferred strategy for the freight and trade needs of Western Australia,” it said in a recent newsletter.

“In fact, the Westport taskforce does not have any pre-conceived ideas or plans.”

One of its key tasks will be determining the capacity of the inner harbour.

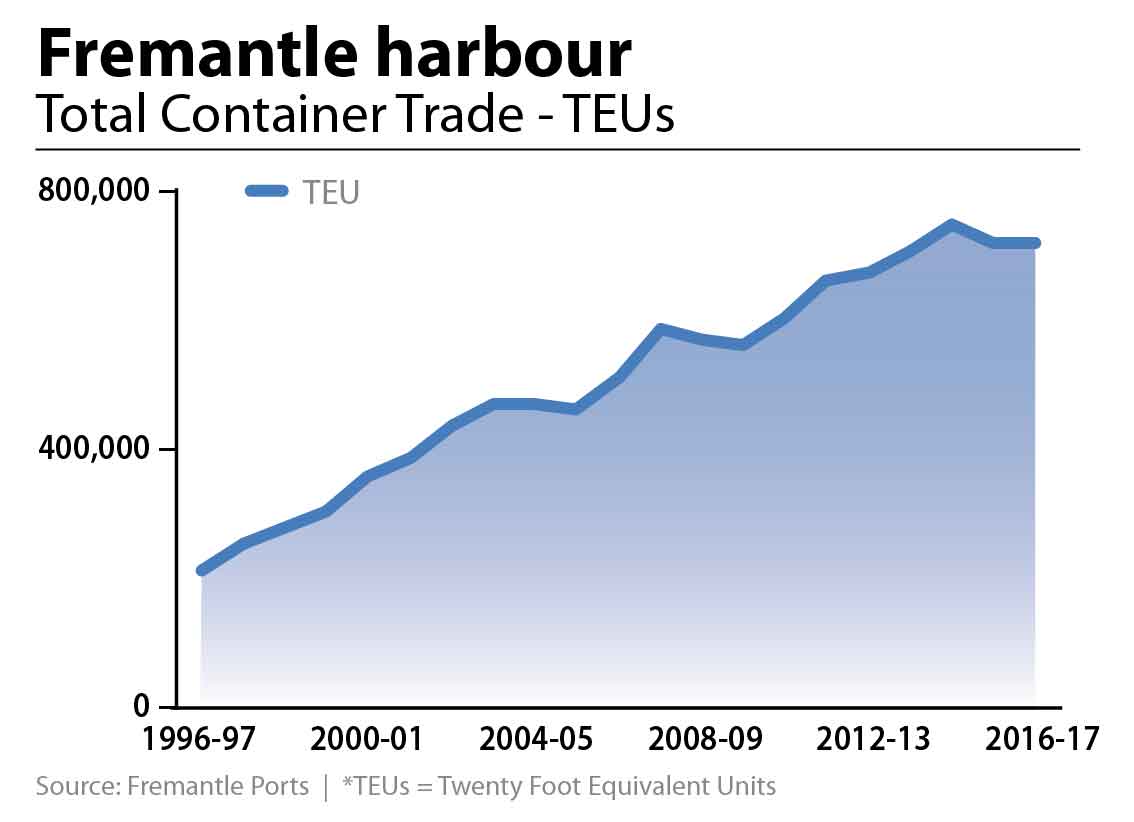

The chart above shows long-term growth in container traffic through the inner harbour to 715,000 TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent units) in 2016-17.

However, its notable that growth has tapered over the past decade. In the 10 years to 2006-07, container volumes grew by 141 per cent; in the next 10 years, volumes grew by just 41 per cent.

The latest figure is well below the peak of 743,000 TEUs in 2014-15.

It is also well below the figure of 1.2 million TEUs, which 10 years ago was seen as capacity.

The Westport taskforce has a different view.

“The inner harbour is capable of handling double the present number of containers,” the taskforce stated in a recent discussion paper.

However, it added that access roads and railway lines were constrained by residential development.

“This means that more traffic to the port results in less amenity for the community,” it said.

Between now and September 2019, when its final report is due, the taskforce will need to pin down exactly how the state should tackle that challenge.