My start point for this doomsday prediction was the negotiation of my first commercial property office lease many years ago. I had previously been nicely insulated from such matters as a solicitor within large corporate firms and was thus surprised to find myself negotiating terms that on the face of the proposed lease were entirely unattractive – until that was you added the impact of the ‘side deed’ which could be compared to someone trying to sell you an extremely expensive bread roll without mentioning that it comes with a free sausage.

As a lawyer used to negotiating and arguing about contract terms, I could not understand the need for two seemingly contradictory legal agreements. Why negotiate the rent at a very high monthly price only to then concurrently offer a massive (say 50%) reduction to that figure? I recall asking the question at the time to be given the simplistic explanation that it was connected to the bases on which the value of commercial office buildings were assessed.

It was an answer that never made sense to me. The value of the commercial offices would naturally be of prime importance to those providing connected finance and surely this entirely widespread practice was known to them – and if so, what was the point of the pretence?

Here is my take on the issue and as a disclaimer it is not an expert one, so I’d be more than happy to have any thoughts or feedback on it. If I’m missing something important then I am very open to correction or education. But it seemed worthy of a quick article.

The banks, in my humble opinion, do appear to know. And here is where we get into full GFC-repeat territory. The 07/08 crisis was caused by the global financial institutions over-inflating the genuine value of large volumes of sub-prime residential mortgages in the US which were then traded around the world as toxic derivatives. We all paid a heavy price for that particular house of cards falling – and it fell once the actual US homeowners were unable to make the loan repayments when interest rates increased.

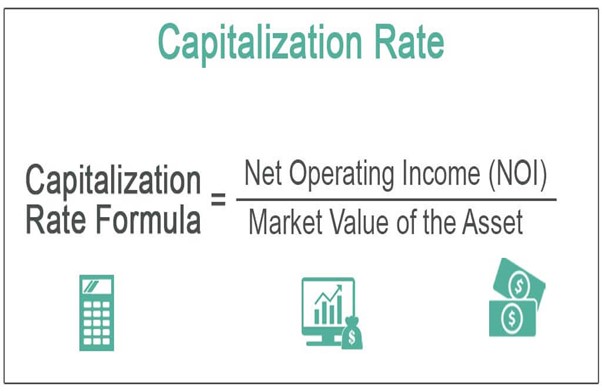

I am reliably informed that for decades now we have seen major Australian commercial property assets being valued, often for the purposes of lending facilities, on a valuation methodology known as the ‘capitalisation rate’, which assesses a property’s capacity to achieve rental income (the relevant calculation being the net operating income divided by the market value/purchase price). Those calculations are therefore heavily reliant upon the per-square-metre rent amounts being secured from the tenants.

But the rent shown on the leases very often has no tangible connection to the rent being paid – sometimes by any of the tenants in that building.

The usual answer to such problems is to rely upon expert valuation assessments – engage the industry specialists to give you the genuine picture.

And therein lies another contributing factor to this concerning scenario: the property valuers know that ‘side deeds’ are entirely commonplace across the industry, they often can tell they are relevant to a commercial property that they are being asked to professionally value, yet they may not be provided with a copy of those agreements in conducting the valuation using the capitalisation rate.

Yep. You read that right. And how do they ignore perhaps the most important pieces of evidence in undertaking a valuation based, at least in part, on rental income? Well, they expressly acknowledge in their reports that they have not reviewed any side deeds or additional lease terms that might be in place and qualify their reports with suitable disclaimers to address the risk of being held liable for such oversight.

I am also reliably informed (I did do some research…) that the commercial property valuers use the argument that to force a tenant or property owner to reveal the existence or contents of side deeds would require a Court order. I am not entirely sure what power or Court process they are referring to, but I do know the logical answer to that problem: it is within the power of the intended lender to specify what information they require to receive in making a commercial decision as to whether to lend money secured by a specific asset. The bank can require disclosure of all such deals and arrangements, as part of its loan application protocol.

But the banks apparently do not demand sight of these side deals. And thus it appears they receive and rely upon valuation reports that they know may be based upon capitalisation rate equations that use manifestly incorrect input data for the rents.

Why? In my humble opinion, because keeping commercial property values artificially high protects the veritable golden asset gooses that underpin our financial market and in particular the World’s largest asset traders, the super funds. It allows banks to keep lending money because there is a sizeable asset pool to lend against. If that asset pool substantially diminishes in value, less lending can happen. And less lending means less bank profits and less returns for shareholders and that ladies and gentlemen is the real game for the modern banking world: shareholder return.

And the model is extremely successful. Highly profitable. Until the unthinkable happens and people do not make the loan repayments. Whilst loans get repaid, the inflated property values create an active market and everyone makes money. But once a large volume of loans go into default because the cost of borrowing goes up, we know from 07/08 that its judgment day.

Very large entities, as we see in the construction industry, can still dramatically crash. Size alone for large property groups will provide no magical shield to insolvency. The bigger they are, the harder they fall. And underpinning those dramatic potential collapses will be our super funds.

Perhaps I am missing some underlying commercial or economic justification for the practice. But my lawyer spider sense was actively engaged the first time that I dealt with the concept firsthand and signed two very different agreements for the same office lease. There are many well-worn phrases concerning things looking and sounding like dogs or possessing distinctive aromas. And this practice seems to fit into those analogous boxes.

If I am right, the commercial property sector is replete with knowingly over-valued assets obtained by lending dependent on those inflated values. A sector drunk on its own success. Perhaps the real question is when we will all have to suffer the hangover. Given the ultimate likely victims being the proverbial mum and dad investors, is there perhaps a need for more regulation?