ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL: The growth in household disposable income provides a graphic illustration of the effect of 25 years of technological change and investment in WA. This article is part of a special series to mark Business News' 25-year anniversary.

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL: The growth in household disposable income provides a graphic illustration of the effect of 25 years of technological change and investment in WA. This article is part of a special series to mark Business News' 25-year anniversary.

The Western Australia of 25 years ago would be largely unrecognisable to some millennials and those in generation Z, so significant and widespread have been the changes.

The most striking differences are technological, as fax machines gave way to digital connectivity and widespread internet access, mobile devices provided instant communication worldwide, and self-driving iron ore trains began to criss-cross the far north of the state.

That take-up of technology, an upskilling workforce and a massive level of investment in the state’s businesses, particularly resources, have all contributed to a significant improvement in the standard of living for the average Western Australian.

In 1993, after-tax income averaged $15,768, or about $29,350 in today’s dollars.

The most recent figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics show that number is now about $51,412, an increase of roughly 75 per cent in 25 years.

At that level, the average Western Australian is better off than the ordinary person in NSW, where mean after-tax income increased 48 per cent over the same period to be about $50,800.

The benefit has been broadly spread around, with the ABS finding mean weekly disposable incomes for the bottom 20 per cent of earners increased about 54.5 per cent in a 21-year period to 2016.

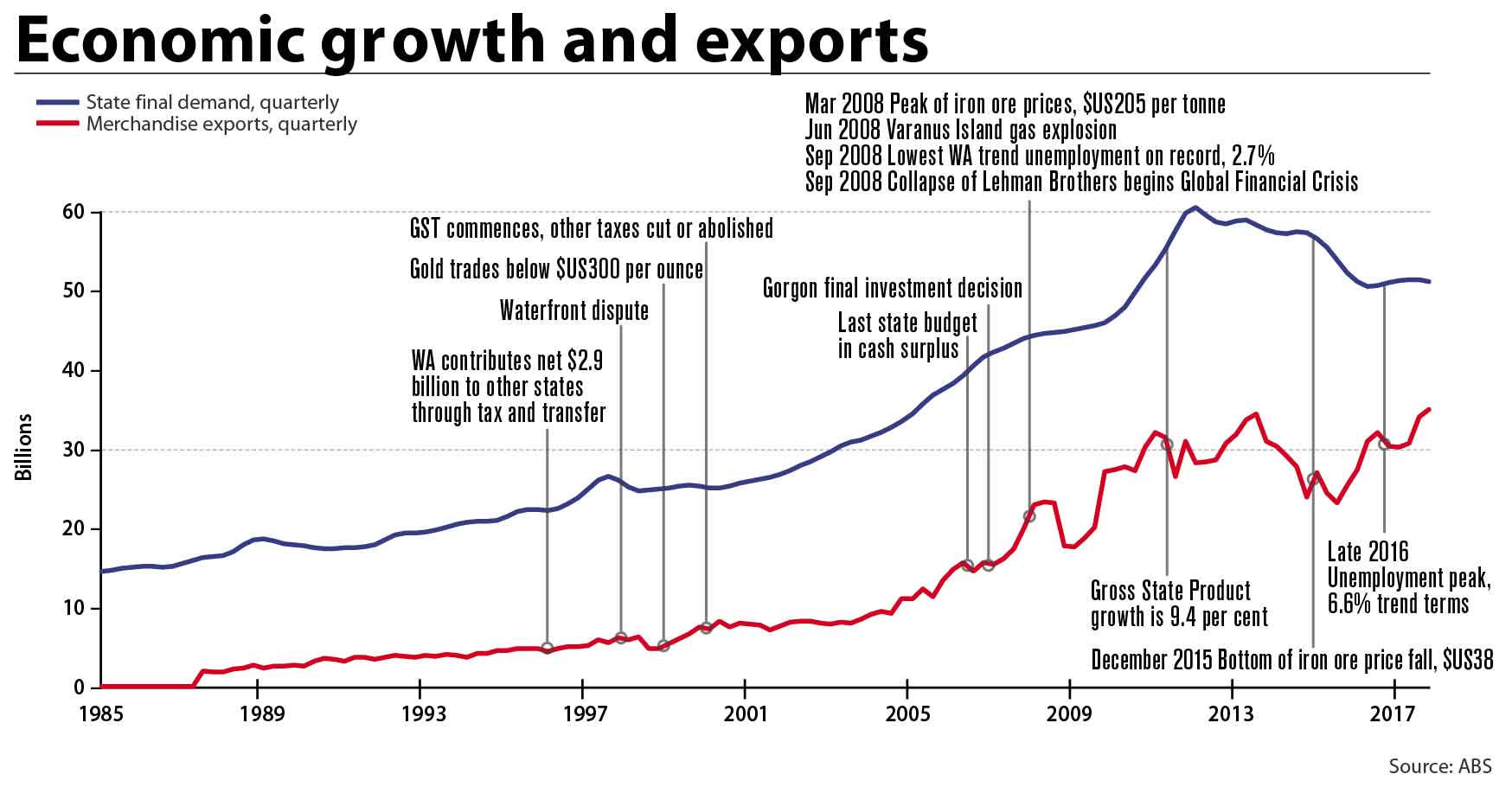

Those numbers come after an economic golden age (see chart), and are despite what has been a tough downturn in recent years.

But the state has outperformed over the longer term.

During the darkest days of the GFC in late 2008, there was a panic across the developed world about a potential repeat of The Great Depression.

In countries such as Spain, unemployment hit a high of 26 per cent in 2013, while in the US it reached 10 per cent in 2010.

Compared with that performance, WA’s jobless rate, which ranged in the post GFC years from 2.7 per cent in September 2008 to 6.6 per cent in 2016, seems miraculously low.

The big driver of that strong employment performance was an investment boom in the resources industry.

Despite a softer economy in recent years, WA is much better off than in 1993.

The state’s net capital stock, or the amount of machinery and other assets used by businesses to produce an income, trebled from about $305 billion in 1993 to $926 billion in June 2017, according to the ABS.

That’s significant because it means workers have more or better equipment to produce output, and so earn higher incomes.

A concrete example is that a small team managing a fleet of automated trucks can move more iron ore than the same number of people driving trucks.

In mining and extractive industries, the capital stock increased more than sixfold to be $414 billion at June 2017, with the level of production of commodities such as iron ore and LNG increasingly significantly as a result (see pages 38 and 42).

Rio Tinto, BHP, Fortescue, Woodside Petroleum, Chevron and Shell led the way with a series of mega projects, the biggest of which was Chevron’s Gorgon LNG plant, which cost $US54 billion.

The investments came as iron ore prices hit highs of more than $US200 per tonne and the oil price as much as $US160 a barrel.

The impact of the resources boom was twofold.

The high level of foreign investment, and growing production of exported commodities, helped Australia avoid recession after the GFC.

The strong commodity prices drove a big improvement in Australia’s terms of trade and a much higher exchange rate.

That improvement in Australia’s external position meant the benefits of the boom were spread across the country, not just concentrated in WA.

Changing employment

Western Australians are working in different jobs now than a quarter of a century ago, with twice as many people likely to work in mining compared with 1993.

About 7.9 per cent of workers in the state are in mining, compared with 3.6 per cent in 1993, according to the ABS.

In raw terms, mining numbers grew from 27,300 employees to 105,200.

Statewide, the number of people employed across all sectors has grown by 78 per cent to more than 1.3 million.

That has been driven in part by population growth, with the working age population 62 per cent larger, at about 2.1 million, in the latest statistics.

But a further big contributor was the increase of women in employment, which rose 95.5 per cent to be 616,200 in September 2018.

Breaking down the roughly 585,000 jobs created across both genders, nearly 60 per cent were full time, although the share of WA workers in part-time employment lifted from 25.3 per cent to be about 31.3 per cent.

Some industries employ a much smaller slice of the WA workforce, with manufacturing experiencing a large decline over the past 25 years.

Only 6.3 per cent of Western Australians are now employed in manufacturing, compared with 9.8 per cent in 1993.

Fiscal challenges

From a public service perspective, the increase in revenue driven by the mining boom years went to higher wages for government staff, a big infrastructure investment program, and interstate.

The last of these was through the GST distribution system, which intends to lift the revenue raising capacity of all states to equal that of the highest state.

That meant in some years WA received as little as 30 per cent of what it might otherwise receive if the GST was distributed on a per capita basis.

One estimate was that as much as 90 per cent of the increased royalty revenue generated by the mining boom was effectively given to other states, with the GST redistribution peaking at about $4.5 billion annually.

State governments did spend plenty, however.

Business News has previously calculated that, in the seven years to 2015, about $46 billion was invested by state governments into assets, including about $6 billion each for Western Power and Water Corporation.

In the same period, public sector salaries rose 44 per cent to be $11.1 billion in the 2015 financial year.

All up, the state government carried debt of $34 billion on June 30 2018, about nine times higher than the level a decade ago.